Reviewed by Charles C. Kolb, Ph.D.

Mrs. Smoot is an intelligence historian who is especially interested in 20th-century cryptology and communication and has published in Cryptologia, Federal History Journal, and Intelligence and National Security; she retired from the Center for Cryptologic History (CCH) of the National Security Agency in 2017. She is also the author of the forthcoming CCH monograph From the Ground Up: American Cryptology during World War I, and a frequent lecturer at the Cryptologic History Symposia, including the May 12, 2022, meeting where she presented “The Case for Parker Hitt as the Father of American Military Cryptology.”

In October 2007, she had heard a talk by a colleague David A. Hatch (now retired from CCH) about Parker Hitt and became intrigued since her husband has actual genealogical connections to Hitt, and she became intrigued in pursuing Hitt’s story. In a way, the resulting book under review here is both a labor of love by a distant relative but one who also is particularly skilled in the history of cryptanalysis and cryptography. The volume was just published this spring in the acclaimed American Warriors Series by the University Press of Kentucky.

Early during her 12 years of research, she read about Parker Hitt in David Kahn’s classic The Codebreakers (New York: Scribner, 1996) where she learned (Chapter 10) about a significant manual Hitt had published in 1916. As she delved into family photographs and correspondence, she also found a book, The Shakespearian Cyphers Examined: An Analysis of Cryptographic Systems Used as Evidence That Some Author Other Than William Shakespeare Wrote the Plays Commonly Attributed to Him (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1957, reissued 2011) inscribed by its authors, William and Elizebeth Friedman, to Parker Hitt dated November 1957: “The father of modern American military cryptology, whose 101-page Manual for the Solution of Military Ciphers guided our early, halting footsteps in the science and launched us upon our careers in the service of our country.” The volume won the Friedman’s the Folger Shakespeare Library literary prize. Hitt’s Manual was the first practical work of its kind in the United States in a century and laid the foundation for America’s impressive cryptologic achievements during the 20th century.

Smoot’s fascinating and detailed biography includes Parker Hitt, “an extraordinary and ingenious man,” his wife Genevieve Young Hitt (seven years his junior), and their daughter Mary Lueise, all of whom worked on aspects of cryptanalysis or cryptography, but remained “shadows on the sidelines” until illuminated by Smoot. Genevieve served as a U.S. government cryptologist, and would “pave the way” for future generations of females in the profession. The story is related in a dozen thorough chapters, accompanied by “Acknowledgments,” “Notes,” a “Selected Bibliography,” a useful and comprehensive “Index,” as well as a cluster of illustrations grouped together following page 150. The early chapters are biographical and genealogical drawing upon public and private records: “Making of the Man,” Making of a Soldier, “Genevieve Young,” and “Making of the Expert” before “To France.”

Parker Hitt was born in Indianapolis, Indiana on August 27, 1878, received his early education there, and enrolled in civil engineering at Purdue University where, as a junior, he enlisted in the Army partly because of patriotism and partly a desire for adventure when volunteers were called for the Spanish-American War. He was already a sergeant in the 2nd U.S. Volunteer Engineers, serving in Cuba and in 1899, commissioned as a 2nd Lieutenant in the 22nd Infantry, and served in the Philippines and also in Alaska. While at Fort Sam Houston, Captain Hitt courted a well-educated physician’s daughter, Genevieve Young, and married her in July 1911. They had a daughter, Mary Lueise, a year later. He attended the Army Signal Corps School at Fort Leavenworth from 1911 to 1912. His final paper on electrical batteries led to the construction of a new field telephone switchboard which he accomplished with fellow students in 1912. The Commandant, Major Edgar Russel, requested that Hitt stay on as an Instructor for the next three years and while teaching there, he would write the Manual by May 1915, then refine and publish it in 1916. The revision incorporated Mexican cyphers. A young admiring 2nd Lieutenant, William F. Friedman, began using the Manual as a text from 1917-1918.

Parker Hitt realized that the official U.S. Army field cyphers and other unofficial systems that were in use were insecure and he designed and constructed the model for a more secure system as a replacement in May 1914, which involved a sliding strip or cylinder and was in use by 1916. In October 1915 he was tasked with cryptographic work but also taught machine gunnery in the Infantry where he developed slide rules to be used to improve distance and accuracy. General Pershing’s Punitive Expedition to Mexico against Pancho Villa followed.

When the United States joined the Allies in the First World War, Parker Hitt was uniquely prepared as a signal officer or in some cryptologic capacity. He had been thinking, writing, and speaking about radio cyphers and other wartime communications and was sent to headquarters in France, crossing the Atlantic on RMS Baltic. His shipmates included Pershing, Patton, and Rickenbacker. In Paris, Hitt supervised the American Expeditionary Forces code room and designed and managed the U.S. communication systems establishing liaison with French and British authorities. His request was also approved to bring American female telephone operators to France to better handle the volume of communications. By July 1918, Parker Hitt was Chief Signal Officer of the First Army. He worked on the Lorraine deception, the Muse-Argonne operation (a 47-day offensive), and the mythical X Army radio deception operation.

Meanwhile, Genevieve remained at Fort Sam Houston where, “at home” (initially for no compensation), she worked on intercepted enciphered messages. Later she would work five and a half day weeks for $85 per month. She met new neighbors who would remain lifelong but distant friends: Captain Dwight David Eisenhower and wife Mamie. After the Armistice on November 11, 1918, Genevieve moved to Winchester, Virginia, while Parker tended to postwar activities in France and the creation of the Third Army, headquartered in Coblenz, Germany. He then, as a 41-year old Major, taught at the Army War College where he worked on carrier telegraphy and reconnected with the Eisenhower family. Betsy Smoot points out the Army failed to capitalize on Parker Hitt’s critical cryptographic skills and encryption work on encypherment systems. Hitt began to contemplate retirement as he returned to the 2nd Division in San Antonio and an Infantry School Refresher at Fort Benning, Georgia. He was appointed to the General Staff in 1926, working in G3 Operations and Training Section, but found the work “boring,” The family moved to “home” in the Shenandoah Valley of Virginia.

In Chapter 8: Commerce, Colonel Parker Hitt retires and accepted an offer of employment from an assistant during World War I, Colonel Richard Sosthenes Behn, who by 1928 had formed a “corporate giant” in New York City: IT&T (International Telephone and Telegraph). Hitt would continue his work on cypher machines inventing seven devices (four patented) before the Stock Market Crash. Behn had bought most of a German radio manufacturer, C. Lorenz AG from the Phillips Corporation in May 1930 but the economic crash results in layoffs for most of the IT&T workforce, except Hitt. He invented the teletypewriter cipher machine, but his latest machine with notched wheels was seen by Friedman and his superior Major Crawford, but was rejected by the Army and State Department as “not secure,” However, Hitt’s machine contributed to Friedman’s thinking in designing the SIGABA machine and the ten-wheel German TUNNY, Parker Hitt’s health declined and he had a heart attack in January 1932; he also had pseudo-anginas in 1928, 1931, 1935, 1938, and 1940. He went to Front Royal, Virginia to recuperate where Genevieve’s fruit farm was near failure from drought. He held no full time job from 1932 through 1939 but continued to write and guide the nascent American Cryptogram Association (ACA).

Friedman lectured about the Signal Intelligence Service during the summer of 1938 and Parker Hitt, sensing war, requested return to active duty September 9, 1939 –the response came in September 1940. At age 62 he failed his medical examination but the “old boy network” intervened and he was certified for limited duty at Fort Hayes near Columbus, Ohio and established a communications relay center for the corps area headquarters. At age 65 he was official released from duty. Mary Lueise held several positions among 10,000 other women at Arlington Hall Station but had no desire to be a professional cryptologist.

The final chapters in Smoot’s book, “The Old Soldier” and “Legacy,” detail Parker and Genevieve’s health issues, the move to Front Royal, Virginia where she passed February 6, 1963 and Parker died on March 2, 1971. Mary Lueise looked after her father until the end and she died January 25, 1997. A recommendation to Chief of Staff George C. Marshall to award Parker with the Legion of Merit had been rejected following World War II. He was inducted into the Military Intelligence Corps Hall of Fame in 1988, and in 1995, Hitt Hall at Fort Huachuca was named in his honor. His work directly influenced William and Elizebeth Friedman, who referred to him as the “father of modern American cryptology” and he was inducted into the NSA/CSS Cryptologic Hall of Honor in 2011.

Betsy Rohaly Smoot has honored the memory of the Hitt family and Parker Hitt’s service to the infantry and innovative work on U.S. military communications and more recent intelligence services in her lovingly detailed book. It is well worth reading.

Readers will find only mentions of the Hitt family in Jason Fagone’s biography of Elizebeth Smith Friedman: The Woman Who Smashed Codes: A True Story of Love, Spies, and the Unlikely Heroine Who Outwitted America’s Enemies (New York: Harper Collins, 2017): Genevieve p. 71. Parker and the Manual pp. 71-72, 76-77, 105. Likewise in another biography, Lisa Mundy’s Code Girls: The Untold Story of the American Women Code Breakers of World War II (New York: Hachette Books, 2017): as expected Elizebeth. S. Friedman p. 58, 59-66, 67, 68-70, 71-73, 77, 87-88, 101, 180-181, 341; but also Genevieve Hitt pp. 67-68 and Parker Hitt pp. 67-69.

Dr. Kolb is a Golden Life Member of the U.S. Naval Institute.

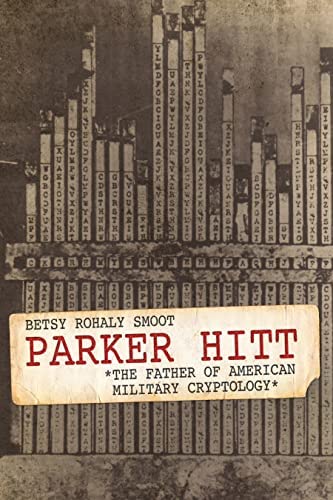

Parker Hitt: The Father of American Military Cryptology. By Betsy Rohaly Smoot (Lexington: University of Kentucky Press, 2022).