By Kyle Nappi

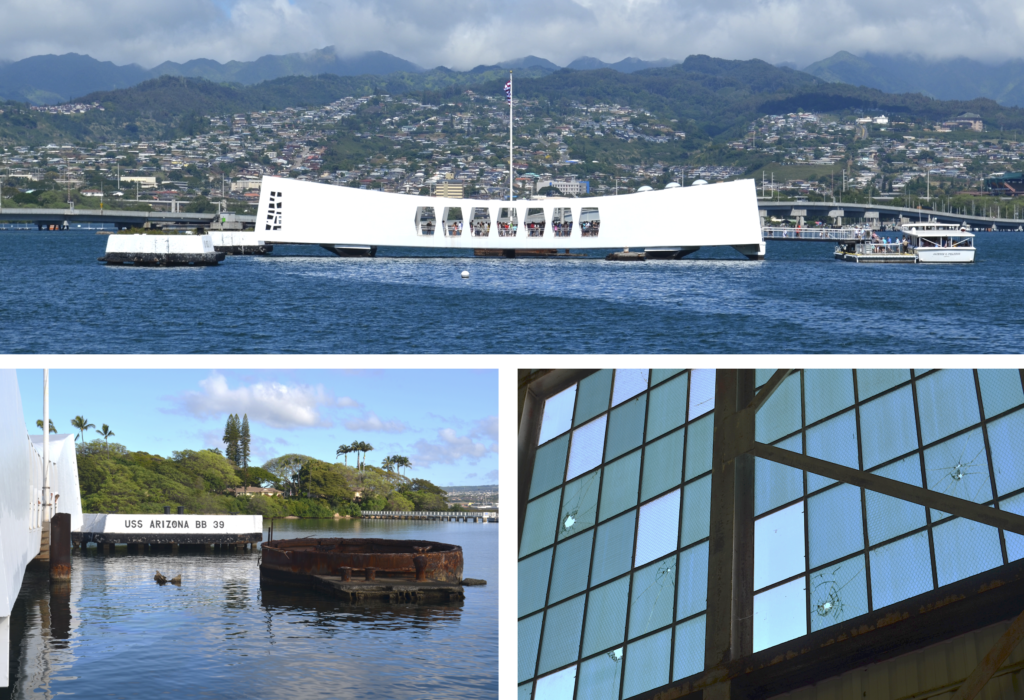

Three years ago, I visited the oil-leaking wreckage of the battleship USS Arizona (among other solemn locations) in Pearl Harbor, Hawaii. Now, eighty years since America’s Day of Infamy, I pause and reflect on those hallowed grounds in Oahu as well as the dwindling number of military veterans who witnessed and survived the Japanese surprise attack.

Captivated by the events of Pearl Harbor since a young age and inspired to learn directly from those who witnessed the attack, I embarked on what became an ambitious decade-long quest to interview the rapidly fading Allied and Axis combatants of the Second World War. Among the more than 4,500 biographical accounts I compiled, some of the most memorable and thought-provoking perspectives originate from the handful of Pearl Harbor veterans I had the honor to engage.

The first Pearl Harbor veteran I met – Edward Hannah, Sr. – gave a keynote address in my small central Ohio hometown, relating his experiences as an enlisted sailor onboard the destroyer USS Blue. The most “iconic” Pearl Harbor veteran I met – James Leavelle – gained worldwide notoriety long after his service as a Storekeeper on the destroyer tender USS Whitney. On November 24, 1963, this sailor-turned-Stetson-wearing Dallas Police Department detective was handcuffed to Lee Harvey Oswald at the time of the assassin’s fatal shooting.

While it is unknown exactly how many Pearl Harbor veterans are left, the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs estimates that, of the sixteen million Americans who served throughout the Second World War, only 240,329 were still alive as of September 2021.[1] Therefore, with witnesses rapidly dwindling, I think it is only appropriate to pay homage on this eightieth anniversary and amplify the reflections of those who bore witness to that fateful Sunday morning on December 7, 1941.

Some of the most vivid memories shared among these old sailors pertained to their whereabouts in the moments leading up to the surprise attack. “Lying in my bunk [and] listening to state-side broadcast of radio. Song was ‘I Don’t Want To Set The World On Fire,’” remembered Lester Johnston, a Fireman First Class onboard the destroyer USS Perry.[2] Meanwhile, Radioman First Class Edward Stone had just relieved the radioman on duty onboard the ammunition ship USS Pyro. “He reported that all circuits were very quiet and only received one routine message,” Stone described. “He returned in about ten minutes and said look out the radio room door and see some funny looking planes banking around about fifty to one hundred feet off the water heading for battleship row.”[3] Moored off Ford Island onboard the battleship USS Utah, Pharmacist’s Mate Second Class Leonid “Lee” Soucy recalled, “I happened to be looking out of a porthole in the direction that the Japanese planes appeared.”[4]

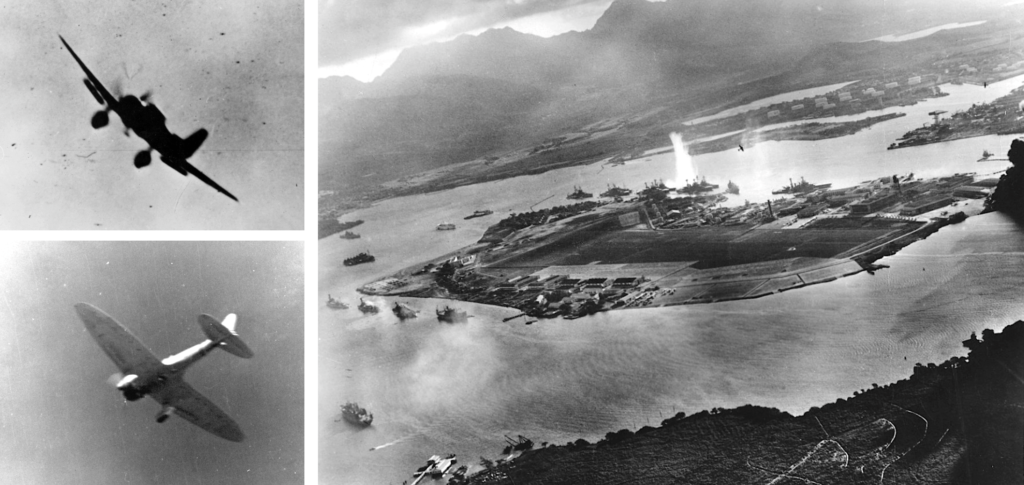

An atmosphere of confusion permeated the harbor as these aircraft began to release their lethal ordnance on the unsuspecting naval fleet. Seaman First Class Clinton Westbrook, Sr., normally assigned to the fourth gun turret onboard the USS Arizona, remembered the opening salvoes while performing a boat-run onboard a fifty-foot motorized craft to the neighboring battleship USS Nevada. “The first strafing plane…made us think the U.S. Army ‘Fly Boys’ were pulling a drill. The second strafing plane was banked and showed the red ‘meat ball’ on its wings.”[5] Westbrook, like all occupants within the harbor that day, made haste and dodged the murderous torrent of enemy fire from above. “Explosions were everywhere as was the Japanese planes.”[6]

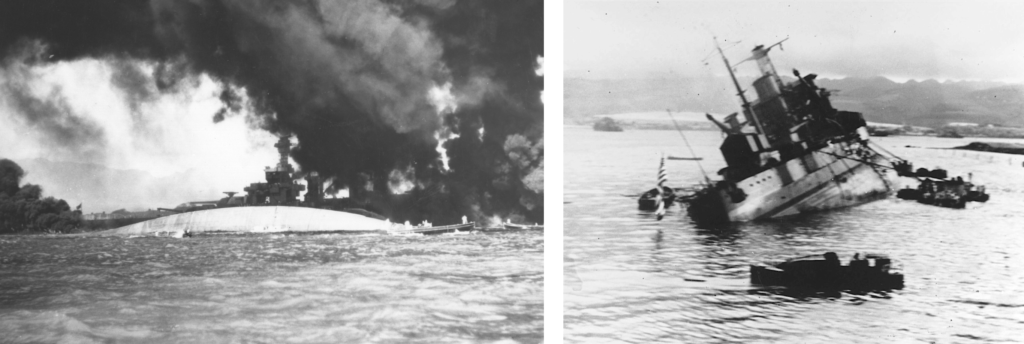

The first wave of Japanese torpedo bombers, dive bombers, and fighters – one hundred and eighty-one aircraft in all – achieved complete surprise as they swarmed over Oahu.[7] Among their key targets were the U.S. Navy’s eight battleships moored on both sides of Ford Island. Within the forward dynamo room of the battleship USS Oklahoma, Fireman Third Class Chester Jankowski searched for a way topside after his ship absorbed hit after hit in rapid succession during the first few minutes of the attack. “Five to eight torpedoes,” Jankowski remembered. With her port side torn open, the doomed Oklahoma quickly capsized into the harbor’s shallow waters. The battleship had already listed forty-five degrees by the time Jankowski exited from a second deck aft hatch. “She rolled over in twenty minutes,” Jankowski shared. “Four hundred and twenty-nine died.”[8] Of these fallen sailors, eighty-three remain unidentified eight decades later.[9]

As Jankowski and others abandoned the sinking Oklahoma, across Ford Island the sailors onboard the Utah would soon meet a similar fate. Flooding from two direct torpedo hits in the span of five minutes quickly overwhelmed the battleship, which, incidentally, had been demilitarized and converted into a target ship for the U.S. Navy.[10] “When the attack began, I went to the wardroom where I worked,” recalled Mess Attendant Third Class Clark Simmons, an African American sailor onboard the Utah. “I knew life jackets were around and it was a high part of the ship I could get off.”[11] As he made his way off the capsizing Utah, Simmons was struck by a bullet from a passing Japanese plane; fortunately, he mustered the strength to swim ashore to Ford Island. Likewise, Pharmacist’s Mate Second Class Soucy managed to escape the sinking Utah. “After swimming ashore,” Soucy reflected, “another pharmacist’s mate and I were picked up by two officers in a jeep and taken to BOQ ([Bachelor Officer Quarters]) on Ford Island to tend to wounded and severely burned sailors and marines.”[12]

Despite the horrific carnage unfolding throughout the harbor, countless sailors manned their posts and valiantly fought back. Awoken from his bunk onboard the destroyer USS Patterson, Chief Machinist’s Mate Louis Campese recalled, “they got us up on deck and I went to my gun station. We started firing at the planes.”[13] Meanwhile, aboard the USS Pyro, Radioman First Class Stone hurried to his battle station as a sight setter on one of the ship’s fantail 5-inch/51-caliber guns, which he described as “old World War One broadside guns that could not elevate above thirty degrees. Not good against aircraft and required fourteen men to man.”[14] In an after-action report, the USS Pyro’s commanding officer noted a near miss that rocked the ship. “One dive bomber approached from the port bow at [an] altitude of five hundred feet and released a bomb which landed on the concrete dock about twelve feet from ship’s side amidships…”[15] Stone still remembered this incident. “We had a full load of ammo onboard and we had a bomb that missed the ship by twelve feet. Talk about luck. Our gunners hit that plane and it was smoking badly…I’m sure that he never made it back two hundred miles to his carrier.”[16]

Assigned to the port side 5-inch/25-caliber anti-aircraft (AA) battery onboard the cruiser USS New Orleans, Gunner’s Mate Second Class James Edwards shared perhaps one of the most interesting eyewitness anecdotes from the Pearl Harbor attack. “I was the Hot Shellman [who] caught the hot shell casings after the gun fired and threw them clear,” he described. With electrical power cut to the New Orleans, her sailors resorted to manually loading, aiming, and firing the AA guns, which, thanks to the ingenuity of her crew, were all in action within a span of ten minutes.[17] “One of our Chief Gunners Mates,” Edwards recalled, “formed a line of men from the ammunition magazines to the guns and they passed these eighty pound shells…Our Chaplain [Lieutenant Junior Grade] Howell Forgy went up and down this line slapping these men on the backs and shouting ‘Praise the Lord and pass the ammunition.’”[18]

The most enduring imagery of the Pearl Harbor attack remains the bombing of the USS Arizona. Radioman Third Class Glenn Lane noted he was between fifty to one hundred feet away from the falling bombs as he “fought fire on aft part of ship, starboard side.”[19] “The main [bomb] that exploded the ship,” explained Quartermaster Third Class Louis “Lou” Conter, also onboard the Arizona, “went through five decks to the lower handling room and exploded over one million pounds of powder used to fire the forward turret guns…The bow lifted out of the water thirty to forty feet and settled back all on fire from [the] mainmast forward.”[20] Seaman First Class Westbrook was enroute back to the Arizona onboard his small motorboat in Battleship Row when this inferno erupted. “We were approaching her and [were] about forty to fifty yards off her port quarters when she exploded. The concussion lifted our fifty-footer out of the water, turned us around one hundred and eighty degrees, and dropped us back into the water.”[21]

Blown overboard from the explosion, Radioman Third Class Glenn described swimming “in oil covered water to USS Nevada. [I] climbed aboard and helped fight fires and care for wounded.”[22] Seaman First Class Westbrook, meanwhile, made use of his still-seaworthy fifty-foot boat. “We did rescue work, pulling men out of the floating/burning oil and took them to Ford Island,” he reflected. “We made three round trips under strafing attacks each time…I was wounded twice.”[23] Of all the casualties incurred during the Pearl Harbor attack – 2,403 killed in action– roughly half were attributable to the USS Arizona, most of whom were junior enlisted sailors.[24]

The events of December 7, 1941 remained an unforgettable memory in the long lives of my aforementioned correspondents. Notwithstanding the horrors they endured, they were very receptive to making their stories known. In fact, they all dedicated their twilight years to amplifying their Day of Infamy experiences to countless audiences. Sadly, all but one of my correspondents – Lou Conter of the Arizona, now one-hundred-years-old – have passed away. Lee Soucy, Clark Simmons, and Glenn Lane were subsequently interred alongside their fallen shipmates in the underwater remnants of the USS Utah and USS Arizona. May we honor their service and sacrifice in observance of the eightieth anniversary of the date which will live in infamy.

Sources:

[1] “WWII Veteran Statistics: The Passing Of The WWII Generation”, The National WWII Museum, www.nationalww2museum.org/war/wwii-veteran-statistics, accessed November 27, 2021. [2] Lester Johnston, Letter to Kyle Nappi, Newark, Ohio, November 28, 2005. [3] Edward Stone, Letter to Kyle Nappi, Syracuse, New York, November 7, 2007. [4] Leonid Soucy, Letter to Kyle Nappi, Plainview, Texas, March 11, 2007. [5] Clinton Westbrook, Sr., Letter to Kyle Nappi, Altoona, Florida, September 27, 2005. [6] Ibid. [7] “Overview of The Pearl Harbor Attack, 7 December 1941”, Naval History and Heritage Command, www.history.navy.mil/research/library/online-reading-room/title-list-alphabetically/p/the-pearl-harbor-attack-7-december-1941.html, accessed November 27, 2021. [8] Chester Jankowski, Letter to Kyle Nappi, Swansea, Illinois, August 6, 2005. [9] David Vergun, “DOD Identifies Most Remains of Those Killed on USS Oklahoma”, U.S. Department of Defense News, September 17, 2021, www.defense.gov/News/News-Stories/Article/Article/2777391/dod-identifies-most-remains-of-those-killed-on-uss-oklahoma/. [10] “Battleship Row”, Pearl Harbor National Memorial, National Park Service, www.nps.gov/perl/learn/historyculture/battleship-row.htm, accessed November 29, 2021. [11] Clark Simmons, Letter to Kyle Nappi, Brooklyn, New York, September 29, 2005. [12] Soucy, Letter, 2007. [13] Louis Campese, Letter to Kyle Nappi, Utica, New York, December 30, 2005. [14] Stone, Letter, 2007. [15] “USS Pyro, Report of Pearl Harbor Attack”, Naval History and Heritage Command, www.history.navy.mil/research/archives/digital-exhibits-highlights/action-reports/wwii-pearl-harbor-attack/ships-m-r/uss-pyro-ae-1-action-report.html, accessed November 26, 2021. [16] Edward Stone, Email to Kyle Nappi, October 21, 2007. [17] “New Orleans II (CA-32), 1934-1959”, Naval History and Heritage Command, www.history.navy.mil/research/histories/ship-histories/danfs/n/new-orleans-ii.html, accessed November 30, 2021. [18] James Edwards. Letter to Kyle Nappi. Louisville, Kentucky. June 19, 2007. [19] Glenn Lane, Letter to Kyle Nappi, Oak Harbor, Washington, August 5, 2005. [20] Louis Conter, Letter to Kyle Nappi, Grass Valley, California, December 28, 2005. [21] Westbrook, Letter, 2005. [22] Glenn Lane, Letter to Kyle Nappi, Oak Harbor, Washington, August 5, 2005. [23] Westbrook, Letter, 2005. [24] “The Attack on Pearl Harbor – December 7, 1941”, Naval Historical Foundation, Thursday Tidings, December 6, 2019, navyhistory.org/2019/12/the-attack-on-pearl-harbor-december-7-1941/.Kyle Nappi is a national security policy specialist in the Washington, D.C. metropolitan area and an independent researcher and writer of military history (chiefly the World Wars), having interviewed ~4,500 elder military combatants across nearly two-dozen countries. In 2020, Mr. Nappi’ wrote three research articles for NHF – “Die letzten Wölfe: Veterans of the Kriegsmarine’s U-Boat Force”, “Divine Wind: Reflections From Two Kamikaze Veterans”, and “Target, Hiroshima: Witnesses To The Dawn Of The Nuclear Age.” Mr. Nappi is also a recipient of the NHF’s Volunteer of the Year award for efforts to return World War II photographs and memorabilia seized on the island of Saipan to families of fallen Japanese combatants.