Reviewed by Jeff Schultz

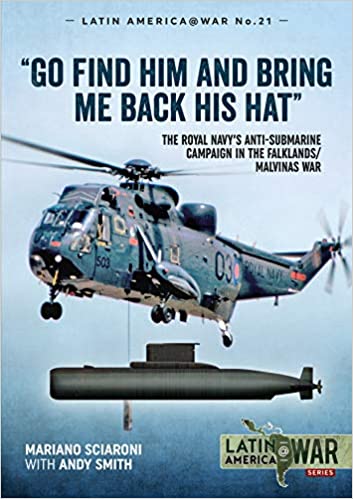

Mariano Sciaroni and Andy Smith’s “Go Find Him and Bring Me Back His Hat”: The Royal Navy’s Anti-Submarine Campaign in the Falklands/Malvinas War is an important look at the relatively obscure rivalry between a few Argentine diesel submarines and the Royal Navy’s anti-submarine defenses such as helicopters, warships and the Royal Air Force’s maritime patrol aircraft which tried to limit the threat to the Task Force vessels as they transited to the disputed islands. Most related books focus on the land and air aspects of the war instead of the exhausting battle above and beneath the sea fought by tired crews trying to find elusive diesel submarines. Above all else, the book highlights the challenges of waging modern war against a non-peer rival like Argentina and the considerable British losses suffered defeating them.

A lawyer by trade, Sciaroni has authored two books and a number of articles on Argentine military history, while Smith brings his research knowledge of the Falklands War to this interesting project.

The 72-page A4 format book is divided into ten brief chapters with references and sources, well-supported by many black and white photos, detailed color maps, interview snippets, primary sources and a selection of color plates featuring aircraft and submarines. The range of images and the attention to detail they exhibit will prove valuable not only for naval history buffs but also modelers.

In particular, taking the perspective of an Argentine submariner sheds new light on the challenges they faced, and their limitations, delivering a much-needed alternative viewpoint to the typically British retellings of this post-imperial war taking place amidst the larger Cold War conflict. Since the authors still draw heavily from the British experience in addition to lesser-known Argentine content, the reader can gain a richer sense of both sides’ methods.

The great value of this work derives from its attention to details which may remain unaddressed in more land or air-centric narratives. “Go Find Him and Bring Me Back His Hat” covers the tactics employed by both sides, as well as the technical limitations and variety of equipment being operated, equipment malfunctions and failures, operational helicopter losses, usage of sonobuoy/dipping sonar, the general uncertainty of tracking submarines among the objects both biological and non-biological littering the deep, the importance of interservice cooperation and the grinding monotony of protecting high value assets against attack.

There are a number of supporting tables, such as “Royal Navy Escorts” (p. 26) which lists all twenty-two British escort vessels that did their best to protect carriers, logistics vessels, and high value units (HVU). Additionally, “Anti-Submarine Attacks During Operation Corporate” (pp. 38-40) provides an exhaustive list of the breadth of attacks during the campaign, ranging from Mk 46 torpedoes to Mk 10 Limbo mortar salvos. A table detailing “Weapon Employment Against Submarine ARA Santa Fe” (p. 45) specifically is also noteworthy.

The graphics in the color plates section show the different anti-submarine warfare (ASW) tracks of specific encounters from April to May, 1982, along with the “Argentine submarine patrol areas” and the British ASW screen formation used to counter potential threats (pp. iii-viii). The Royal Navy also had to contend with a surreptitious Soviet presence, consisting not only of surveillance vessels like the Zaporozhye but also of potential submarines shadowing the effort since a possible World War III was always in the offing (p. 59). It was to counter the Soviet threat that the Task Force carried nuclear depth charges, which thankfully went unused (p. 33).

Despite the scale of the British ASW effort, they really only faced one submarine in the Falklands Islands area of operations, the German-built Type-209 ARA San Luis with a second submarine threat in the South Georgia area in the form of the American-built ex-Balao class ARA Santa Fe. A third submarine, the Type-209 ARA Salta sat in port during the war, unable to contribute. Against one modern and one aging diesel submarine the British brought a large collection of escorts along with two aircraft carriers, the HMS Hermes and Invincible. In addition, five submarines, including nuclear-powered “hunter-killers”, operated in the region. One such sub, the HMS Conqueror, sunk the cruiser ARA General Belgrano (formerly WW2-era ex-Brooklyn class USS Phoenix), with two Mk8 torpedo strikes. This resulted in the loss of over 300 Argentine sailors and prompted the Argentine Navy to suspend all offensive actions from May 2, 1982 onwards (p. 29). British submarine fears were also justified, as ARA San Luis claimed attacks on Royal Navy vessels on two different occasions, but the advanced SST-4 torpedoes failed to hit their targets.

The story of the submarine ARA Santa Fe is detailed among other vignettes, and ranks as one of the more interesting clashes in recent history. When a hostile but aging diesel boat was spotted and engaged by missile-armed British helicopters in the waters off South Georgia Island, the crew of the ARA Santa Fe (formerly WW2-era ex-Balao class USS Catfish) was sent to reinforce the existing Argentine garrison and found themselves tasked with sneaking past the British cordon in a modernized GUPPY II version of a World War II submarine. Ultimately, the British Wasp helicopters of the icebreaker HMS Endurance fired nine wire-guided AS.12 missiles at the Santa Fe and five hit home. This, combined with a Wessex HAS.3 helicopter’s depth charge attack disabled the Santa Fe enough to end its involvement in the war (42-48). Though Argentina is certainly not the only nation to operate second-hand warships from countries like the United States, this confrontation ranks as one of the more fascinating of the campaign.

Mariano Sciaroni and Andy Smith’s “Go Find Him and Bring Me Back His Hat”: The Royal Navy’s Anti-Submarine Campaign in the Falklands/Malvinas War provides important material, from both the British and Argentine points of view, pertaining to the 1982 Falklands/Malvinas War, and in particular the “cat and mouse” anti-submarine game played out in the dark and unforgiving waters of the South Atlantic. Readers may be surprised to hear of the large amount of ordnance used to prosecute potential sub-surface targets, among other details which presents this heretofore neglected aspect of history as a rich tapestry of desperate efforts to stem a worrisome undersea foe.

Jeff Schultz is an Associate Professor of History at Luzerne County Community College.

“Go Find Him and Bring Me Back his Hat”: The Royal Navy’s Anti-Submarine Campaign in the Falklands/Malvinas War (Mariano Sciaroni and Andy Smith, Helion & Company, Warwick, Great Britiain, 2020)