By Carol Mauer Butler

“When I get a letter, my heart takes a very skip and then starts thumping. After you’re finished reading the letter you feel good. You’re at peace with world. You like it and it likes you.”

These were the sentiments a WWII navy man expressed in a letter to his mother. Over 200 of the letters that Bernard H. Mauer (Ben) wrote from 1941-45 survived, letters written during a golden age of military letters home. In compiling these letters, documents, and photos from his time in the war, I’ve learned the incredible power of a letter—which surpasses in some ways the phone calls, skypes, texts, and emails currently available to our enlisted men and women.

What letters lack in immediacy, they make up for in longevity. Composed with love and treasured by receiver and writer alike, these letters lay in wait 75 years before I would publish them in a volume, a project that has revealed the world of my father’s youth and captured this important slice of time in our nation’s history. Letters, though items of a moment, have more permanency than our current electronic data, which have often proven to be less reliable. Though some curated items may last forever, many dissolve into the ether, lost when platforms change, when hard drives crash, when servers delete a user, or just when sheer volume overtakes organization.

The deliberate quality of a letter, the act of sitting down to compose once a week, adds to the importance of these documents. It took concentrated effort, which was often not easy. The evidence of the struggle is in the letters themselves because letters have a tendency to be quite meta. In Ben’s letters much space given over to the difficulty in composing letters, the challenge of censorship, and even the abuse he received of having to function as a censor himself. The pleas for more letters are almost overwhelming. And to receive letters, he had to write them as well, no matter how difficult.

But the primary takeaway on the metacommentary about letter writing is not so much the struggle he experienced but the value of the letters. Letters were like gold: “The letters you sent, mom, I’ve read over and over again.” His frustrated need for the connection to his loved ones is palpable: “News from home is the biggest thing for me. To know that someone back there still loves you. Most of last month’s mail got jammed up somewhere, no one knows where.”

Who was his audience? My father wrote to girlfriends, cousins, and friends he met on leave, but the three bodies of letters that were saved were to his parents (Marie and Fred), his brother Arnie (an Army Air Force sergeant), and Roz (his brother’s girlfriend, then fiancée, and then wife). These close family members held onto the letters and gave them to my father when he came home from the South Pacific. He then kept them for decades, browsing through them from time to time, especially so in the last decade of his life in the 1990’s as he reflected on various 50th anniversaries and contributed to new articles and commemorations.

But at the time he writes these letters, their future importance is not a consideration. Ben is very cognizant of the impact of his letters on his family, continuing the playful, teasing relationship he had. He aims for an off-the-cuff casual style, unstudied, full of contractions and slang. He experiments with different closing lines: “Your sidekick,” “Love to you kid,” “Devotedly yours,” “Am your good boy.” He ends one in a mock flourish: “From ‘brave’ Bennie, the floatingest cork on the molten sea of hell” —that after surviving the sinking of his oil tanker SS Tamaulipas by a U-boat attack off the coast of North Carolina. He was between training with the US Maritime Service and becoming a cadet at Kings Point Merchant Marine Academy when he signed on for this risky duty. Despite that obvious exception—or because of it—, one of his goals in writing was to reassure his loved ones—especially Mom—that he was fine, he was safe, all was well.

Their letters in turn must have been full of similar assurances; he references tales of fish being caught off Long Island, news of the cross-town rivalry between the Yankees and the Dodgers (the Brooklyn Bums), and notes about aunts and uncles and cousins.

But through this veneer of cheer and comfort, an honest voice rings through, the young man missing home but eager for adventure. Some of this honesty is generated by the time-bound quality of the letters, a major appeal to me. As he writes, he doesn’t know the outcome of the war or any of the myriad of actions taking place around the globe; history is happening as he writes. When allowed by the censors to finally write of significant action, the past tense is barely past. We feel the fear and excitement of the kamikaze attacks in Leyte Gulf, the exhaustion of non-stop hours at GQ, and the amazement topside at the star shells and flashes of gunfire.

Those wanting to know more about U-boat attacks or the liberation of the Philippines can find plenty to read in history books by experts who have thoroughly researched the subject—and indeed, I have plunged fully into research myself on those two topics. But such books still can’t replace a first-hand account conveyed by a man we feel we know because he has revealed his loves, gripes, desires, regrets, ambitions, and concerns through scores of letters.

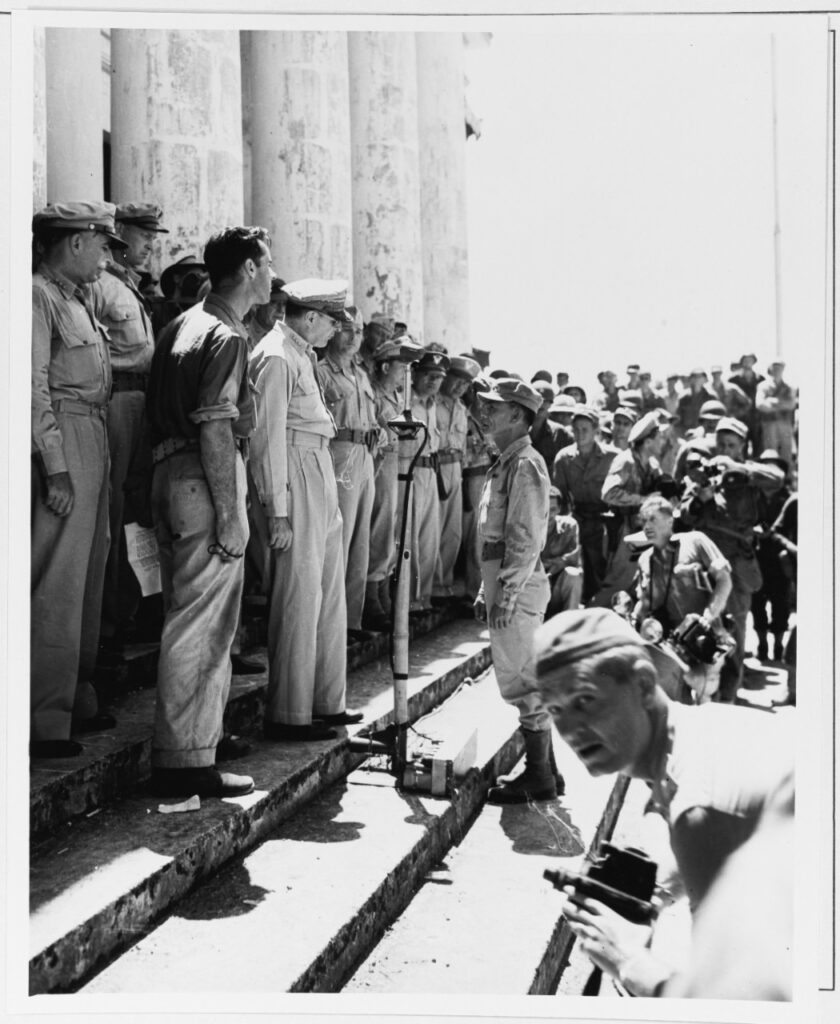

The need to keep pumping out letters in order to get letters also provides information that historical accounts don’t often supply: a portrait of the humdrum, day-to-day life of a sailor/officer on call and ready for action—but not seeing any action. Ben’s ship in the South Pacific was the USS Blue Ridge, a command ship for Admiral Daniel E. Barbey, commander of the Seventh Amphibious Force. The Blue Ridge was the site for plans, preparations, communications; it had photography labs and mass printing capabilities. This ship was mostly left behind during the taking of the islands by the amphibious craft (with the remarkable exceptions of Leyte Gulf and Lingayen Gulf).

So, instead, to fill the pages, we hear about card games, ship baseball teams, USO shows, inspections, pranks, wrestling, hiking, reading, swimming, singing, record playing—and watching movies every night. Bogart shows up in too many of them, he notes. Ben was one of the men in charge of procuring new movies to keep the 500 men aboard ship diverted in the evening. He had screens put up at both ends of the ship, and he would risk the mosquitoes ashore to trade for movies that wouldn’t get him booed when he brought them back. Such minor history provides the backdrop of the life of the regular man in the navy, the minutiae not covered so much by the history books.

So despite the many obstacles of getting letters out—never-ending work in the engine room, censorship restrictions, writing in cramped and hot quarters at times, brain not functioning (“My thoughts plod along like a stubborn mule. I can’t speed them up no matter how much I may whip them.”), and an irregular delivery service—he persevered. And I am enriched by having this epistolary history of my father, his life and times during his early twenties.

With Love and Affection, Your Sailor Ben: WWII Letters of B.H. Mauer, a 400-page volume of letters written by Navy Lt. (jg) Bernard H. Mauer, 1943 graduate of Kings Point Merchant Marine Academy.