By Kyle Nappi

At first glance, “kamikaze veteran” will undoubtedly read as an oxymoron to most Americans. Best parodied in an episode of Curb Your Enthusiasm, producer/actor Larry David muses how one can be a kamikaze pilot and yet still be alive. My own introduction to this concept is traceable to a handful of biographical articles I had read within The Japan Times. There, these elder Tokubetsu Kogekitai (or, “Special Attack Unit”) aviators recounted their military experiences as well as the life they enjoyed after the war. Captivated, I sought to learn from those still alive.

Seventy-five years later, the imagery of Imperial Japan’s devastating kamikaze attacks remains an inexorable part of World War II’s Pacific Theater. Ultimately, the direct hits, or damaging near miss impact hits of these aircraft claimed more than 15,000 Allied causalities and an estimated 466 ships either sunk or damaged. For some, not even the passage of time could erode the clarity of such dramatic events. Daniel Kitchen, a U.S. Navy Lieutenant who served onboard Landing Craft Tank (LCT)-746, recalled one such kamikaze attack near the island of Iejima during the Battle of Okinawa in May 1945. “I witnessed the conclusion of this pilot’s flight and tried to imagine what went through his mind.” Kitchen then shared with me an excerpt of an essay he had penned on this event:

“I watched as the pilot died…instantly and in vain. I hope that he was distracted by gunfire and concentrating on precision flying…and never noticed the deserted decks, unmanned guns and empty bridge of his target. It was LST 808, wrecked and abandoned, gutted by a torpedo attack a few days earlier, but with decks and superstructure intact, still resting upright on the coral sand in the shallows of our anchorage.”

Like Kitchen, numerous U.S. sailors had also shared with me their own encounters with kamikaze aircraft seeking to menace their ships and crew. Yet, would it be possible for me to contact such surviving pilots? Where would I start? How could I navigate not only the language barrier but also potential cultural sensitivities of those vanquished combatants? Of the nearly 4,500 elder military veterans I would ultimately interview over the span of a decade, those with an allegiance to Imperial Japan constitute a small fraction. Unlike their former Japanese counterparts, more than two hundred Wehrmacht veterans were indeed very receptive to my correspondence and queries. Among them was nonagenarian Hans-Joachim “Hajo” Herrmann, once a colonel in the German Luftwaffe and confidant of Reichsmarschall Göring.

Inspired by the psychological fear imposed by kamikaze attacks during the Battle of Leyte Gulf in 1944, Herrmann devised a similar tactic to unnerve Allied bomber crews over Europe. Ultimately hoping to compel the Allies to suspend their bombing raids, albeit, if only temporarily, Herrmann sought to buy more time for the production of Germany’s jet fighters, ballistic missiles, and other Wunderwaffe (or, “Wonder Weapons”). On April 7, 1945, more than 180 unarmed Me-109 and Fw-190 fighters were dispatched into the skies over Germany to deliberately ram their aircraft into American B-17 and B-24 bombers. Less than two-dozen such bombers were ultimately brought down.

Seventy-five years later, the exploits of the Third Reich’s Sonderkommando Elbe pilots in Europe are all but overshadowed by Imperial Japan’s larger, longer, and costlier kamikaze campaign throughout the Pacific. Yet, I had still managed to identify and correspond with the brainchild behind Germany’s obscure squadron of doomed one-way flyers. Surely, I could just as easily connect with the handful of ever-dwindling Japanese pilots who held the rare distinction of “kamikaze veteran.” Ron Werneth, author of Beyond Pearl Harbor: The Untold Stories of Japan’s Naval Airmen and Fall of the Japanese Empire: Memories of the Air War 1942–1945, offered to me some candid thoughts on the matter. “Most Americans don’t realize is that these Japanese veterans are very private people. It took ten years of my life to get to know them and I had to move to Japan to do that.”

Luckily, I began to make inroads among a network of military scholars, journalists, government officials, and others like Werneth who each undertook a similar research effort. The Zero Fighter Pilots Association – a Japanese organization comprised of surviving World War II Mitsubishi A6M Zero (or “Zeke”) aviators – introduced me to Masami Takahashi. An Assistant Professor at Northeastern Illinois University, Takahashi had produced the documentary The Last Kamikaze: Testimonials from WWII Suicide Pilots. Appreciative of my interests, Takahashi applauded my efforts and shared that a Japanese veteran I previously engaged through the Zero Fighter Pilots Association “was a good friend of my deceased father who was also trained as a kamikaze pilot.”

Later, I became acquainted with Risa Morimoto who produced the documentary Wings of Defeat, which also amplified the stories of surviving kamikaze pilots. Like Takahashi, a direct family connection inspired Morimoto’s interest. “My uncle served in the military,” she explained. “[He] trained as a kamikaze.” At the time of our initial dialogues, Morimoto was serendipitously only a few weeks away from traveling to Japan to reconnect with the kamikaze pilots featured in her documentary. To my surprise, she even volunteered to personally initiate my long-distance correspondence interview with Takehiko Ena, one of the pilots. What incredible luck!

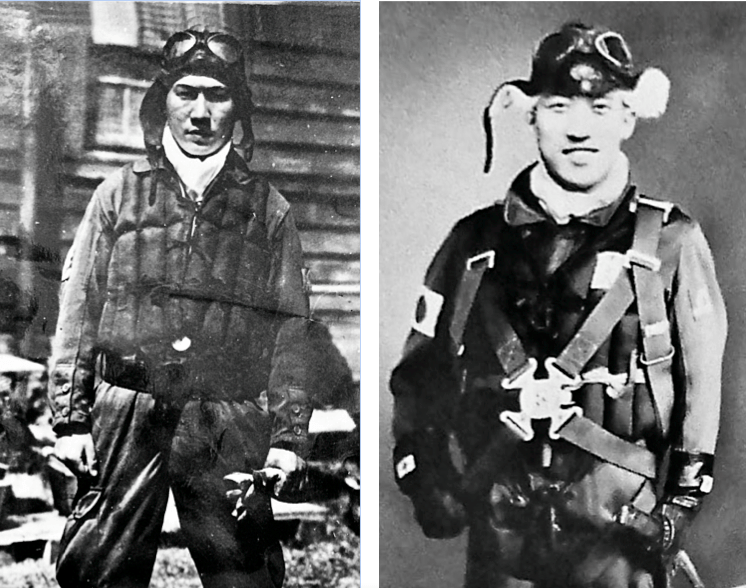

A native of Tokyo, Ena had been conscripted into the Imperial Japanese Navy in 1943. In the spring of 1945, Ensign Ena joined a kamikaze unit at twenty-two years of age and well aware of the risks. “At the emergency of my country,” he wrote, “I, enduring my fear of death, resolutely carried out self-sacrifice.”

Subsequently assigned to a Seiki Squadron of the Hyakurihara Naval Air Group in Japan’s Kagoshima Prefecture, Ena awaited his orders to join Kikusui (or, “Floating Chrysanthemums”). Throughout this two and a month campaign, Imperial Japan would dispatch more than 1,400 kamikazes to disrupt Allied ships during the Battle of Okinawa. These attacks would ultimately claim the lives of nearly 4,900 U.S. sailors. “My duty was the kamikaze attack of the US ships near Zanpa Point, on the west coast of Okinawa,” Ena shared with me. “The drill was to hit a US ship from a low altitude…in my plane.”

Despite limited flying experience, Ena became a pilot of one of only seven available aircraft within his unit: the Nakajima B5N torpedo-bomber. Commonly dubbed the “Kate” by Allies, these three-person aircraft were equipped with a 1,760 lb bomb and enough fuel for a one-way mission. Given the scarcity of aircraft throughout Japan in the final months of the war, kamikaze units would often receive older, below average equipment for their largely inexperienced flyers. Indeed, mechanical problems were quite common and forced many pilots to abort their missions or return shortly after takeoff. For Ena, and a handful of others, such malfunctions would become their salvation.

On April 28, 1945 – the fourth large-scale Kikusui mission – Ena’s aircraft struggled to stay airborne and subsequently crash-landed at a nearby airbase due to engine failure. On May 11, 1945 – the sixth large-scale Kikusui mission – Ena made yet another attempt but fate would continue to spare his life. “On the way to the target,” he shared, “my plane had a trouble and landed on the sea near a solitary island. I swam for 1 km to the island.” Ena and his crew spent the remainder of the war marooned on Kuroshima, a mountainous six square mile island in the northern Ryukyu archipelago.

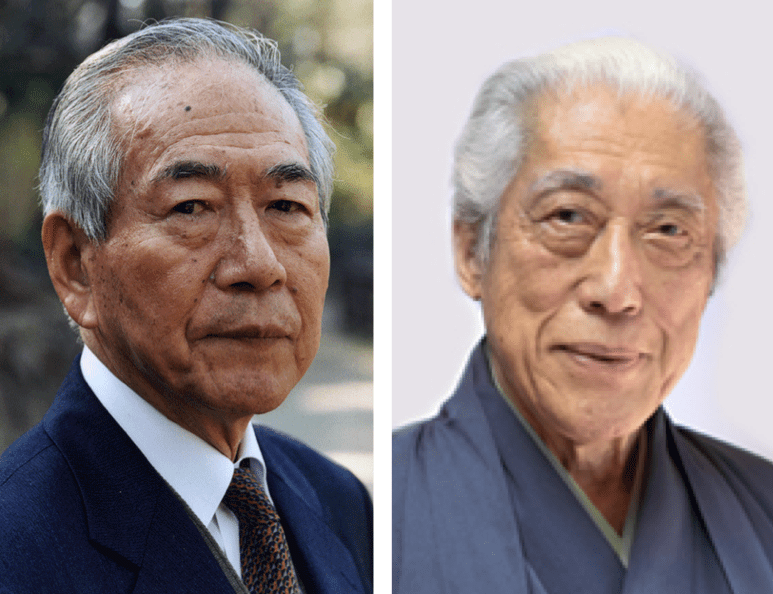

Returning to the mainland at the end of the war, Ena sought to pay tribute to the handful of islanders who ensured his survival. In 2004, exactly fifty-nine years from the date he ditched in the waters off Kuroshima, an eighty-year-old Ena helped unveil the first of three such monuments on the island: a statue of Kannon (or, the Buddhist Goddess of mercy). The following is an excerpt of the engraved text, as translated from Japanese to English, at its base:

“Many Special Attack planes attacked by sea from the western side of Okinawa…by way of Kuroshima in order to avoid enemy fighters waiting for them…Along the way in the skies above Kanmuri Peak here on Kuroshima, they looked back and saw beautifully shaped Mount Kaimon above the horizon receding into the distance. Departing from the mainland full of emotions, they prayed for peace and security for their homeland…they went bravely to faraway floating clouds above the vast expanse of the seas and died for their country…We pray for eternal rest for their souls.”

Ena’s wartime experience is one of many that illustrate the larger statistical record of Japan’s kamikaze pilots. Of the nearly 3,000 sorties launched from October 1944 until the war’s end, roughly a third successfully reached a point in which the pilots could commence an attack upon Allied ships. Meanwhile on the Japanese mainland, thousands more awaited orders that never arrived. This was the case for Sen Genshitsu, the second kamikaze whom I interviewed (albeit via long-distance correspondence much like Ena, though separately).

Born as Sen Masaoki, Genshitsu possesses a rather unique family linage to the sixteenth century founder of a School of Japanese tea known as Urasenke. A native of Kyoto, Genshitu joined the aviation arm of the Imperial Japanese Navy in December 1943 at twenty-one years of age. Enrolled in college at the time, Genshitu explained to me that he was “taken into [the] service at the time of the fourteenth enlistment of student reserves.”

Initially assigned to the Tokushima Air Group in Japan’s Tokushima Prefecture, Naval First Lieutenant Genshitu flew training missions in the Mitsubishi K3M3 high-wing aircraft, dubbed the “Pine” by Allies. Formed in 1942, the Tokushima Air Group groomed flight observers for reconnaissance missions. In March 1945, all trainings were discontinued and recruits were eagerly sought for the newly created kamikaze units. “I volunteered,” Genshitu wrote. “I felt that I would give my life in order for my beloved family to soon be able to exist in a peaceful world.”

Later assigned to a Shiragiku (or, “White Chrysanthemum”) unit within the Tokushima Air Group, Genshitu flew the outfit’s namesake aircraft: the Kyushu K11W Shiragiku. A modest trainer aircraft, the K11W could carry a singular 550 lb bomb and reach a maximum speed of only 140 mph. Certainly not the fastest for a kamikaze strike. Genshitu recalled to me the strenuous, daylong drills of his unit, from practicing aerial diving runs and night flying off Japan’s southern coast. “It was extremely hard training, and even to remember it, I am amazed that I managed to endure it.” Like Ena, Genshitu shared that his targets were U.S. ships of his own choosing near Okinawa.

Genshitu was soon dispatched to an airbase near the city of Matsuyama in Japan’s Ehime Prefecture. There, he hoped to participate in the ninth or tenth large-scale Kikusui missions, launched from June 3-22, 1945. “As a pilot in the kamikaze corps, it was a matter of variously coming and going between the realm of life and the realm of death,” he described to me. While he awaited orders that never arrived, Genshitu watched many of his fellow aviators depart, never to return. “I lost many pals and it all was so sad,” he reflected. “I want never to experience war again.”

In the aftermath of the war, Genshitu returned to his roots and, within two decades, became the fifteenth generational head of Urasenke. “I have been traveling the world, appealing for everyone to achieve ‘Peacefulness Through a Bowl of Tea,’” he explained. “Since coming home alive from the war, I have made more than 300 trips abroad, and been to about 62 countries of the world, to make this appeal of mine for achieving peace.” On July 19, 2011, an eighty-eight-year-old Genshitu – in partnership with the National Park Service and the U.S. Navy – led a sacred Urasenke tea ceremony onboard the USS Arizona Memorial in Pearl Harbor as a gesture of peace and reconciliation between the United States and Japan. Considered a high honor in Japanese culture, this gathering featured several American veterans who bore witness to the “Day of Infamy” seventy years prior.

It is estimated more than 3,800 kamikaze aviators perished during World War II. Perhaps after years of reflection, both Ena and Genshitu discovered and accepted the true mission previously unknown to them in 1945: to live.

About The Author: Kyle Nappi is an Associate at Booz Allen Hamilton, a Fortune 500 management-consulting firm in the Washington, D.C. metro area. In April 2020, the NHF featured Mr. Nappi’s “Die letzten Wölfe: Veterans of the Kriegsmarine’s U-Boat Force” article in Thursday Tidings. Mr. Nappi is also a recipient of the NHF’s Volunteer of the Year award for efforts to return photographs and memorabilia seized on the island of Saipan to families of fallen World War II Japanese combatants.

This article was prepared by the author in his personal capacity. The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official policy, opinion, or position of their employer.

Sources and Image Credits

- Cox, Samuel, “‘Floating Chrysanthemums’—The Naval Battle of Okinawa,” Naval History and Heritage Command, last modified April 3, 2020, www.history.navy.mil/about-us/leadership/director/directors-corner/h-grams/h-gram-044.html.

- “‘Curb Your Enthusiasm’ Kamikaze Bingo.” IMDb, last modified October 16, 2005, www.imdb.com/title/tt0551388/.

- Ena, Takehiko, Letter with enclosures to Kyle Nappi, Tokyo, Japan April 2009.

- Genshitsu, Sen, Letter with enclosures to Kyle Nappi, Kyoto, Japan, March 7, 2009.

- Gordon, Bill, “Kuroshima Special Attack Peace Kannon: Mishima Town, Kagoshima Prefecture,” Kamikaze Images, last modified June 1, 2020, www.kamikazeimages.net/monuments/kuroshima/index.htm.

- “Greetings from SEN Genshitsu (Soshitsu XV),” Urasenke Konnichian Website, accessed June 2020, www.urasenke.or.jp/texte/world/e_usa02/e_usa02.html.

- Huffman, James. “Challenging Kamikaze Stereotypes: ‘Wings of Defeat’ on the Silver Screen,” The Asia-Pacific Journal: Japan Focus, Volume 6, Issue 9, September 1, 2008.

- Kitchen, Daniel, “WWII Japanese Kamikaze Pilots,” E-mail message to Kyle Nappi, January 31, 2009.

- Morimoto, Risa, “WWII Japanese Kamikaze Pilots,” E-mail message to Kyle Nappi, February 10, 2009.

- Ohnuki-Tierney, Emiko, Kamikaze, Cherry Blossoms, and Nationalisms: The Militarization of Aesthetics in Japanese History, University of Chicago Press, 2010.

- Stille, Mark, US Navy Ships vs Kamikazes 1944–45, Bloomsbury Publishing, 2016.

- Takahashi, Masami, “WWII veterans,” E-mail message to Kyle Nappi, January 31, 2009.

- “Tea Offering Ceremony by SEN Genshitsu at the USS Arizona Memorial,” Urasenke Konnichian Website, accessed June 2020, www.urasenke.or.jp/texte/world/e_usa02/e_usa02.html.

- Werneth, Ron. “WWII Japanese Pilots,” E-mail message to Kyle Nappi, February 22, 2009.

Joseph Smith