This article is a reprint from Ready Then, Ready Now, Ready Always: More than a Century of Service by Citizen-Sailors

By NHF Historian Dr. Dave Winkler

Navy nurse Josie Brown reflected on the horrible ordeal that she and her colleagues had to confront in 1918:

The morgues were packed almost to the ceiling with bodies stacked one on top of another. The morticians worked day and night. You could never turn around without seeing a big red truck loaded with caskets for the train station so bodies could be sent home.

The scene Brown described was not behind the front lines in France but at the new Navy Training Station in Illinois along the shores of Lake Michigan. Thousands of regular Navy and Naval Reserve Force recruits arrived there eager to become bluejackets in a growing U.S. Navy. Many went home in coffins. Brown recalled:

We would give them a little hot whiskey toddy; that’s about all we had time to do. They would have terrific nosebleeds with it. Sometimes the blood would just shoot across the room.

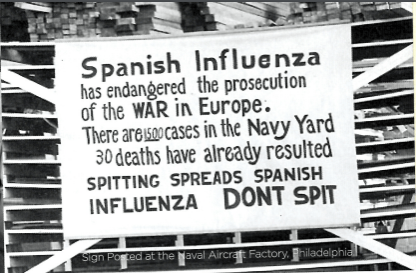

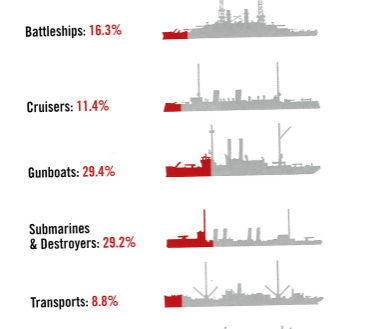

An influenza pandemic had spread around the world. By the time the virus had run its course, an estimated 30 million to 50 million lives would be lost—more than had been lost in World War I. The Navy would not be immune. In 1918 alone, Navy medical personnel, many of them reservists, treated some 121,225 Sailors and Marines who were admitted to Navy medical facilities with influenza. Of these, 4,158 died of the virus. Those treating the illness were not immune. Among the dead were thirty-two Navy nurses. More Sailors were lost during World War I due to the influenza pandemic than to enemy action. For those National Naval Volunteers and Naval Reservists who had been assigned to ships at [sea], the odds of survival were somewhat better. The virus began to go to sea in September 1918, first on the overcrowded transport ships and then on fleet units. The secretary of the Navy’s 1919 report showed the infection rate as follows on the various ship types:

The steam yacht Yacona was one of the unfortunate exceptions. The steel screw vessel, which had been acquired from noted financier Henry Clay Pierce in September 1917, was crewed mainly by Naval Reservists. Between November 17 and 29, 1918, 80 of her crew of 95— 84 percent—came down with influenza.The Navy secretary’s report noted that Yacona, which had been operating from New England, suffered its outbreak after the two waves of the virus had run their course ashore. The first wave spread in early 1918. For example, the report showed that earlier in the year in February the Naval Radio School at Harvard suffered between 350 and 400 cases. Included in this number were 11 cases of pneumococcus-streptococcus. Two months later the Naval Training Camp at San Diego reported similar numbers, with 410 cases and pneumonia affecting a dozen of Sailors.

In July and August a more deadly outbreak of the virus occurred in Europe. The impact could be felt at U.S. Naval Air Stations in Ireland and France,with seven air stations reporting 690 cases. As noted by historian Dudley Knox, a large percentage of the naval aviation component was of the Naval Reserve Force. This deadlier wave hit the United States hard in September. Naval Reservists enrolled in courses at the Naval Training Camp at Pelham Bay Park in New York began reporting symptoms of the flu on September 24. Fortunately, the layout of the camp and the high hygiene standards enforced at that facility blunted the spread of the virus and there were only three reported deaths. At Pelham Bay, the hospital actually reported more cases of injuries due to trainees falling out of hammocks. Elsewhere the story was grimly different. Four days later a severe outbreak began at the Naval Training Camp at Gulfport, Mississippi. By November, this portion of the pandemic had claimed a majority of the estimated 675,000 Americans who would succumb to influenza during a span covering 1918 into 1919.

The Great Pandemic of 1918-1919 is a part of the Navy Reserve legacy for reasons beyond those who suffered the ill effects of the flu – those families who lost a loved one in the service, and the heroism displayed by Naval Reserve Force medical personnel, many of whom lost their lives as a result of caring for the sick.

History of the USNS Mercy

Article from: www.mercy.navy.mil/History.html

The current USNS Mercy, T-AH 19, is the third US Navy ship to bear the name. She is named for the virtue of compassion.

The first Mercy (AH 4) was built in 1907 as Saratoga by William Cramp & Sons, Philadelphia, PA. An Army troop transport in the first nine months of World War I, she was renamed MERCY and converted to a hospital ship at New York Navy Yard, Brooklyn, N.Y.She was commissioned on 24 January 1918. Mercy initially operated in the Chesapeake Bay, homeported in Yorktown, VA. She attended war wounded and transported them from ships to shore hospitals.

On 3 November 1918, Mercy departed New York City, making four round trips to France, returning 1,977 casualties by March 1919. For 15 years following World War I, Mercy served off the East Coast, homeported in Philadelphia. From December 1924 until September 1926, she was in reduced commission. Mercy was loaned to the Philadelphia branch of the Public Relief Administration in March 1934.

The second Mercy (AH 8) was a troop ship built by Consolidated Steel Corp., Wilmington, CA, beginning 4 February 1943. Launched on 25 March 1943, she was sponsored by LT(JG) Doris M. Yetter, NC, USN, a prisoner of war on Guam in 1941. Mercy was converted by Los Angeles Shipbuilding & Drydocking Co., San Pedro, CA.

She was commissioned 7 August 1944, staffed by the Army’s 214th Station Hospital. Departing on 31 August, she arrived in the Leyte Gulf, Phillipines, on 25 October during the Battle for Leyte Gulf. Embarking 400 casualties, she transported the wounded to base hospitals in New Guinea. Over the next five months, Mercy made seven more voyages from Leyte to New Guinea, including transporting the Army’s 3rd Field Hospital from New Guinea to the Philippines in January 1945.

In March 1945, Mercy reported for service in the Okinawa campaign. She and USS Solace (AH 5) arrived on 19 April at Hagushi Beach, Okinawa, embarking patients for four days despite frequent air raids and threat of Japanese Kamikazes. Mercy then transferred the wounded to Saipan, Marianas. She made two more voyages from Saipan to Okinawa the following month. Mercy next made two voyages carrying wounded from Leyte and Manila to New Guinea. She reported to Manila in June for two months duty as station hospital ship.In August, she transported the Army’s 227th Station Hospital to Korea as part of the occupation forces. In October 1945, Mercy returned to San Pedro, CA. She transferred to the U.S. Army on 20 June 1946 for further service as a hospital ship. Mercy received two battle stars for World War II service. She was struck from the Navy List on 25 September 1946.

The third Mercy (T-AH 19) was built as an oil tanker, SS Worth, by National Steel and Shipbuilding Co., San Diego , in 1976. Starting in July 1984, she was renamed and converted to a hospital ship by the same company. Launched on 20 July 1985, USNS Mercy was commissioned 8 November 1986.

On 27 February 1987 , Mercy began a training and humanitarian cruise to the Phillippines and the South Pacific. The staff included U.S. Navy, Army, and Air Force active duty and reserve personnel; U.S. Public Health service; medical providers from the Armed Forces of the Philippines; and MSC civilian mariners. Over 62,000 outpatients and almost 1,000 inpatients were treated at seven Philippine and South pacific ports. Mercy returned to Oakland, CA , on 13 July 1987.

On 9 August 1990, Mercy was activated in support of Operation Desert Shield. Departing on 15 August, she arrived in the Arabian Gulf on 15 September. For the next six months, Mercy provided support to the multinational allied forces. She admitted 690 patients and performed almost 300 surgeries. After treating the 21 American and two Italian repatriated prisoners of war, she departed for home on 16 March 1991 , arriving in Oakland on 23 April. USNS Mercy is currently homeported in San Diego, California.