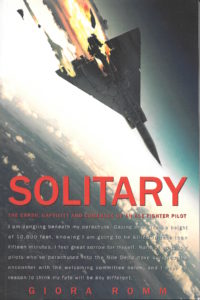

By Giora Romm, Black Irish Entertainment LLC, New York, NY (2014)

By Giora Romm, Black Irish Entertainment LLC, New York, NY (2014)

Reviewed by Cdr. Peter Mersky USNR (Ret.)

Most combat veterans of any country have one great fear, something that sometimes occurs, no matter how they prepare to defend against it: namely, capture by the enemy and imprisonment for an extended duration. In the mid-to-late 20th century, there were many examples of such incredibly ill fortune, especially during the Vietnam War, roughly 1964-1973, where hundreds of Americans, mainly aviators, were incarcerated in North Vietnam for painfully long periods, often as long as five to eight years. Beaten and tortured almost to the point of death, losing 50-100 or more pounds from the meager rations, these individuals had to reach way down inside to survive, and a few could not, dying in the solitary confines of the infamous Hanoi Hilton, or other prisons of the North Vietnamese system. The occasional Medals of Honor, Air Force and Navy Crosses, Silver Stars and Purple Hearts were given to those men who flew home in March 1973 were small compensation for the tragedies they suffered at the hands of their captors. While these stalwarts languished in North Vietnamese prisons, other captives were experiencing the same torturous existence.

Then-Captain (later Major General) Giora Romm of the Israel Air Force had already seen a lot of action, becoming Israel’s first fighter ace during the 1967 Six Day War. He shot down five Egyptian and Syrian MiGs during that brief, but intense conflict that surprised the world. On September 11, 1969, Romm’s Mirage IIICJ was struck by an Egyptian MiG’s cannon fire over Egypt. He ejected at 20,000 feet, an unusually high, and potentially dangerous altitude for such an emergency egress.

Badly injured and as he floated down, he realized he was heading into more danger directly toward a growing group of angry Egyptian farmers and their welcome was not going to be pleasant. After several intense moments of confrontation where he feared for his life, he was rescued by Egyptian army troops to begin what developed into a lengthy, often painful and highly uncertain stay at an unclean facility. Not only was there the expected language problem—Hebrew and Arabic occasionally have minor similarities but are, in fact, two entirely different languages—there was also the apparent animosity between two cultures. None of which was going to help the young Israeli pilot as he struggled to maintain his dignity and security against the constant barrage of questions from the harsh, insistent Egyptian officers.

Romm is not the usual tough-minded, fast-acting fighter pilot, though he does have those qualities in abundance. He is also more cerebral, someone always questioning, searching for reasons, the order of the world around him and why things happen. This highly personal memoir covers a particular five-month period in his eventful life enduring all the physical and mental hardships associated with this most stressful of military experiences. We Americans have focused on the experiences of our POWs in Vietnam and to a lesser extent—perhaps because there were not as many of them in a much shorter time span—of those men and women captured during the 1991 Gulf War and the subsequent conflicts in Iraq and Afghanistan. We might tend to forget that other countries’ warriors have experienced much the same situation. Cut off from their homes and cultures, desperately trying to survive and cope with the harsh realities of dealing with harsh jailers who seem to care very little about their safety or very existence.

Romm is a very private man, and to write these extremely personal stories of his medical and physical torture at the hands of the Egyptians must have taken a great deal of intestinal fortitude that he didn’t know he had. There’s very little aviation association here, except for the fact that he always reminds himself that he is an officer in the Israel Air Force, an ace no less, and it is up to only himself to maintain that dignity even though his appearance and mental state may not seem to support that hard-won status.

This account offers a simple narrative that only occasionally describes the author’s life and family history. He occasionally gives some details in those areas, and they are certainly welcome. Romm is a sabra, a native-born Israeli, whose father left Poland in 1925 at the tender age of 19, came to Israel and made a life for himself and his family in Palestine, as the area was collectively known then. Snippets of his family history and his education and early career in the IAF round out Giora Romm’s history as he takes us with him on his painful journey as a POW.

His language is straightforward and colorful. He is, after all, bi-lingual, able to converse in English as well as Hebrew, having spent considerable time in the U.S. in a variety of assignments, including the Israeli Defense Attache, the senior military representative in the embassy, second only to the ambassador, in the 1990s.

Much of the narrative revolves around the daily contest between Romm and his guards, his struggle to maintain his officer identity while trying to get medical attention and adequate food, as well as a meeting with a Red Cross representative if only to get word back to his family that he is alive. He is severely beaten by what he guesses is a “Sudanese giant,” a huge and powerful individual.

On December 6, 1969, he was transported to a facility and released into the hands of another Red Cross official and ultimately brought home to his anxious family and friends and country, where he is honored as a returning hero. He begins rehabilitation, all the while focusing on returning to flight status, something those around him are not sure he will be able to accomplish. But he does, in time to participate in the 1973 Yom Kippur War as the commanding officer of an A-4 squadron. Not unexpectedly, the Egyptians have learned that Romm is once more in the cockpit, flying against them, and they broadcast an angry message to tell him they are waiting for him. This time, they say, their reception will not be as “benevolent” as the first.

Romm’s description of flying the A-4, a much different aircraft from his delta-winged Mirage, and learning to lead his squadron of eager young men in an increasingly bloody and intense war appears rather suddenly. It is only after he takes a long, hard look at himself and how he feels that he can settle into the assignment given him by high-ranking IAF officers who are also his friends and now need his help, his personality, his experience. This last section gives a lot of detail about flying in the 1973 war never offered in other memoirs. It is well worth reading.

Solitary is the story of one man’s journey from the literal heights of flying at 20,000 feet in pursuit of his country’s enemies to the equally literal and very personal depths of the type of incarceration relatively—thankfully—few men have had to experience. It is a journey worth taking because it allows the reader the chance to safely participate in both the capture and ultimate liberation of the soul and physical well-being of a tiny country’s patriot.

Peter Mersky is a frequent reviewer on aviation history for NHBR.