By David F. Winkler

By David F. Winkler

Historian

Naval Historical Foundation

With the Battle of Jutland centennial in our recent wake, the British Commission for Naval History, The British Commission for Maritime History, and The National Maritime Museum hosted a conference titled “The First World War at Sea, 1914-19” on June 3-4, 2016, at the National Maritime Museum in Greenwich, England.

Given the location of the conference and focus of the subject in British higher education, it was no surprise that British scholars made up the majority of those in attendance. Not surprisingly, many aspects of Jutland were covered ranging from the historiography, performance of the opposing fleets, personal experiences, lessons learned, and the underwater archaeological legacy. Other themes scholars explored included operations in the Mediterranean including the ill-fated Gallipoli Campaign, Anglo-American naval diplomacy, countering the U-Boat threat, and the development and use of new technologies.

A contingent of approximately a dozen American historians was on hand to present perspectives from the “other side of the pond.” Some of these scholars included Annette Amerman of the Marine Corps History Division who discussed Marine Corps aviation in the Great War, Jesse Tumblin of Boston College who explored the Royal Navy’s relationship and control of empire naval assets prior to the war, Eugene Beiriger of De Paul University who explained Anglo-American naval relations and the U.S. Naval Act of 1916, Bradley Cesario of Texas A&M who examined a contentious relationship between the Admiralty and the British press, and Norman Friedman who challenged arguments that it was the implementation of convoys that defeated the U-boat menace.

U.S. naval leadership was the focus of papers presented by trio of Yank scholars. Dennis Conrad of the Naval History and Heritage Command closed out the final first day session in the lecture theater with the paper, “Were they Really So Unprepared: Josephus Daniels and the US Navy Entry into World War I. ” Conrad addressed assertions made by Rear Admiral William S. Sims following the war that accused the Navy Secretary of dereliction of duty and incompetence that led to the loss of 2.5 million tons of allied shipping. In coming to Daniels defense, Conrad explained the career motivations of the American officer corps of that era, rebuking an assertion made in the opening keynote address made by Dr. Nicholas Rodger of All Souls College at Oxford that American officers saw the Prussians as role-models, becoming militaristic and intolerant of civilian leadership. Conrad called Rodger out, saying that U.S. naval officers were much like those in other fields (doctors, engineers) in the Progressive era who sought to professionalize and become more efficient and effective.

U.S. naval leadership was the focus of papers presented by trio of Yank scholars. Dennis Conrad of the Naval History and Heritage Command closed out the final first day session in the lecture theater with the paper, “Were they Really So Unprepared: Josephus Daniels and the US Navy Entry into World War I. ” Conrad addressed assertions made by Rear Admiral William S. Sims following the war that accused the Navy Secretary of dereliction of duty and incompetence that led to the loss of 2.5 million tons of allied shipping. In coming to Daniels defense, Conrad explained the career motivations of the American officer corps of that era, rebuking an assertion made in the opening keynote address made by Dr. Nicholas Rodger of All Souls College at Oxford that American officers saw the Prussians as role-models, becoming militaristic and intolerant of civilian leadership. Conrad called Rodger out, saying that U.S. naval officers were much like those in other fields (doctors, engineers) in the Progressive era who sought to professionalize and become more efficient and effective.

In defending Daniels, Conrad made a convincing case that given the political constraints he faced in a Wilson administration that had been determined to keep America out of the war, Daniels performance was actually “commendable; and that the U.S. Navy’s performance at the beginning of the war was strong and timely.”

Concluding his presentation, Conrad anticipated being challenged by the two American Sims scholars in the audience, David Kohnen of the Naval War College and Chuck Steele of the U.S. Air Force Academy. However, during discussions following that evening over a few pints, both scholars concurred that Sims, who had returned Newport following the war to again serve as the president of the Naval War College, displayed insubordinate behavior.

Reflecting after the conference, Steele observed: “I thought Conrad’s presentation was outstanding. While all of the papers addressing American participation in the Great War were tremendously useful in gaining a better understanding of this nation’s role in the maritime dimensions of the war, the emphasis on Daniels and Sims added depth to the breadth of coverage. Indeed, Conrad’s presentation was essential in establishing a more thorough/ appropriate context for understanding Sims and his role in helping to organize the American naval effort.”

Placed on an all-American panel to open the second day, the two Sims scholars provided attendees additional insights about a fractured American naval leadership situation at the beginning of the conflict that featured blurred responsibility divisions between the General Board, the Navy Secretary, the newly established Chief of Naval Operations, and the Commander in Chief of the Atlantic Fleet. Enter William S. Sims, who had been promoted to Rear Admiral but awaited authority to don the uniform, and served as the recently appointed president of the Naval War College. As such, he was in position to be called on to liaison with the British in preparation of America’s entry into the war. With America declaring war just before his arrival to the mother country, Sims created his own command authority within an evolving naval hierarchy.

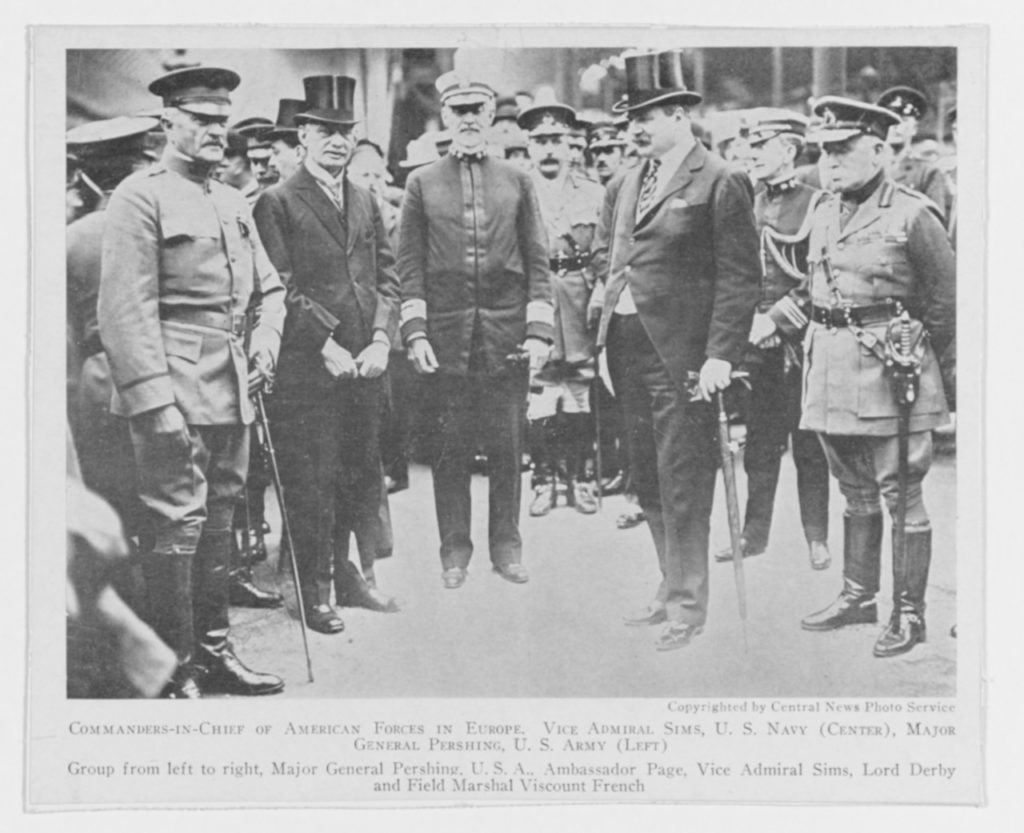

This image was originally taken on 8 June 1917, upon Pershing’s arrival. Note that he arrived in three star status and Sims is standing in the uniform he had made which features two stars. Pershing was two years junior to Sims by lineal precedence, but received his promotion to four stars while Sims received his promotion in July to three stars (with the promotion back dated to May according to the register). In essence, Pershing always outranked Sims as the AEF commander, but Sims held the chair as senior naval representative on the Allied Naval Council in London. (NHHC Photo # NH 52790)

After Steele provided a broad perspective of how Sims contributed to the war effort, Newport historian Kohnen presented his paper, “The ‘London Flagship:’ Admiral William S. Sims and Anglo-American naval collaboration in the First World War.” Kohnen provided the nitty-gritty of the personal relationships that Sims had developed previously with British counterparts that enabled him to pioneer “American ties with the Royal Navy, and in coordinating U.S. Navy operations with intelligence.”

Having arrived in civilian attire and still not authorized to wear the uniform of an admiral, Sims had one made up and he assumed the title of “Commander in Chief, U.S. Naval Forces in Europe.” He subsequently established a headquarters building at Grosvenor Square that he dubbed “The London Flagship” following British shore-establishment naming conventions.Over the next two years, Sims exerted command authority that never existed on paper. That he was not fired for insubordination, reinforced Dennis Conrad’s assessment of Navy Secretary Daniels who appreciated the critical role Sims played in enabling the U.S. Navy to join the war effort.

In his closing remarks, Kohnen discussed the impact of the World War I UK-US command relationship experience on many of the staff officers whose names would loom large during Worlds War II. Asked to join a toast after the war the proposed the U.S. Navy join in an alliance with the naval forces of the British Empire, Ernest J. King would raise his glass and heartily concur and declared that the alliance’s headquarters would be in Washington. Indeed, Kohnen invoked the name of future American Commander in Chief of the United States Fleet during World War II when he closed stating the alliance effort during World War II was that of “A King’s Navy.”

At the conference, Dr. Winkler presented the paper “Manning up the U.S. Fleet: the Naval Reserve Force and National Naval Volunteers.” During his remarks he noted that the banner head for the Naval Historical Foundation’s Pull Together newsletter hailed from the slogan shared between British and American Sailors stationed in Queenstown during the Great War.