“I go along with somebody who says that when Samoa heard that the US government was at war with Japan, the call came around and they offered their hands to help.”

Tuala Sevaaetasi, Former Fitafita Guardsman

By Matthew T. Eng

The proud history of the American Samoan people traces back over 3,000 years, long before any islander saw their first naval vessel or merchant ship. The native population had a long held history of seafaring and pottery making along the archipelago, living undisturbed off the sea and land under the leadership of the Fa’amatai, the chiefly governing authority of the Samoan islands.

European contact with Samoan islanders came in the eighteenth century. The Dutch and French were the first to vie for a foothold in the tropical paradise. This eventually led to a series of violent backlashes between European explorers and Samoans. Tensions calmed in the nineteenth century with the introduction of Christian missionaries. This stability led to a growth in settlers and military personnel on the islands. Trade and education began to prosper. The United States soon came to know the islands well. American whalers hunting in the sperm whale hunting grounds stopped at the island chain for foodstuffs and provisions during the height of offshore whaling in the Pacific. Commodore Charles Wilkes and the United States Exploring Expedition stopped off in the Samoan Islands in 1839 to survey the region. Two vessels of the same expedition, USS Flying Fish and USS Peacock, were involved in a brief bombardment of Upolu in 1841 following the murder of an American sailor.

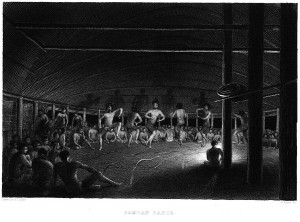

Samoan Dance, Charles Wilkes, Narrative of the United States Exploring Expedition during the years 1838, 1839, 1840, 1841, 1842. Volume 3, 1845 (Image via Smithsonian)

The island chain was not immune to the myriad international rivalries that would eventually carve out large swaths of territory in the name of empire near the beginning of the twentieth century. Disputes and disagreements between unified Germany and the United States eventually came to a head. Officials in Washington, eager for a slice of territory in the South Pacific to show the flag under the Mahanian-like notion of sea power, purchased the chain of islands known today as American Samoa in the 1899 Tripartite Convention with Germany. The eastern set of territories (Germany partitioned the western half of the island chain now the Independent State of Western Samoa) included five main islands and two coral atolls.

The island itself occupies a tiny piece of the South Pacific. As one naval officer pointed out in his assessment of American Samoa, the 290 mile-long island chain is easily fond by drawing a line on a map from Hawaii to New Zealand.

Naval Administration

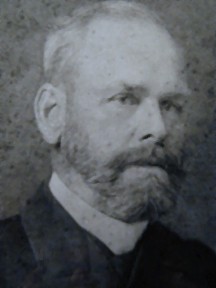

The United States Navy began to manage the affairs of American Samoa in 1900. Commander Benjamin F. Tilley arrived at Pago Pago harbor to establish the territory’s new naval administration. A new naval station was established at the harbor, known as Naval Station Tutuila.

Under the direction of the U.S. Navy, Tilley took on the role of Governor of American Samoa. Other administrative posts within the “Island Government” were given to Navy officers and enlisted men. Governors were appointed directly by the President, and were directed to preside over all legislative, executive, and judicial matters on the islands. Military Governors like Tilley worked closely with the matai, Samoan tribal chiefs, to ensure the everyday niceties of the “Stars and Stripes” did not personally interfere with their own long-held rituals and traditions.

Commander Tilley, a career officer with combat experience during the Spanish-American War, created an island control with two central governing institutions, a judicial system and the Fitafita Guard. In the native Samoan language, the word fita translates to “courage.” Others within the indigenous population translate the term to “soldier.” When placed together, the casual observer of Samoan culture gets a good sense of the unit’s importance. According to Dr. Robert W. Franco, an expert on Samoan/Pacific affairs at Kapi’Olani Community College, the Fitafita guard was set up by the U.S. Navy to “enforce court decisions and generally maintain order.” Members of the Fitafita guard were placed in the naval reserve.

In the early years, the Navy handpicked the Fitafita Guard. Young natives and elites were attracted to the prospect of service. Others came to join the ranks of the Fitafita band for their love of music. The guard soon carved out their own military enclave in the South Pacific, serving both the U.S. Navy and their own people under a banner of mutual respect and admiration. The men of the Fitafita proudly served “with a full heart,” according to former Guardsman Tuala Sevaatasi. The Fitafita Guard had many of the same rights and responsibilities of regular enlisted personnel. Fitafita were given regular Navy pay as well as 20% overseas pay. They were not, however, permitted to serve outside of the home islands at sea, which made them more of an honor guard and ceremonial band than fighting unit. One source stated that some Fitafita guardsmen were given sea duty on an ocean-going tug during the beginning of the outfit’s operation.

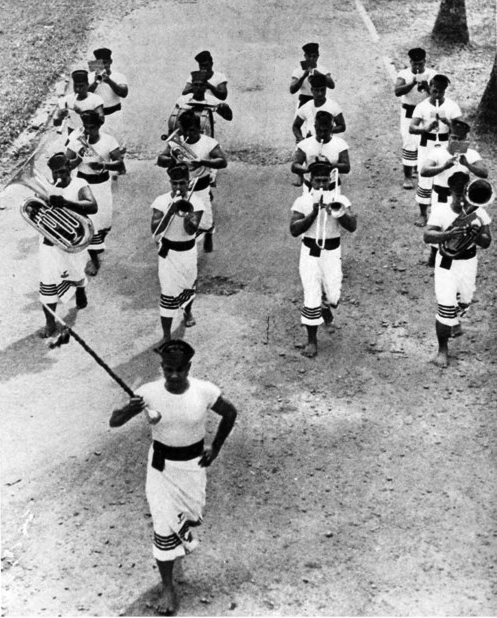

The prestige of becoming a well-respected member of Samoan society drew many indigenous men to service, especially their musicians. The impressive seventeen-piece Fitafita band developed musical expertise, becoming a large influencer on the importance of blending Samoan and American culture together. Navy musicians from the United States were sent to Pago Pago to teach and train the Fitafita how to organize a band. They quickly caught on. Seen in several surviving photographs today, their military drill discipline resembled the world-renowned Marine Corps band. Many Fitafita were also highly proficient with the rifle, often besting competitive teams from visiting militaries. This short excerpt in Modern Samoa: It’s Changing Government and Changing Life discusses the impact and importance of the Samoan-born unit:

“These performed duties as seamen and bandsmen, and the example of their life has been a major shaping force upon the local native youth.” (Modern Samoa: It’s Government and Changing Life, 133)

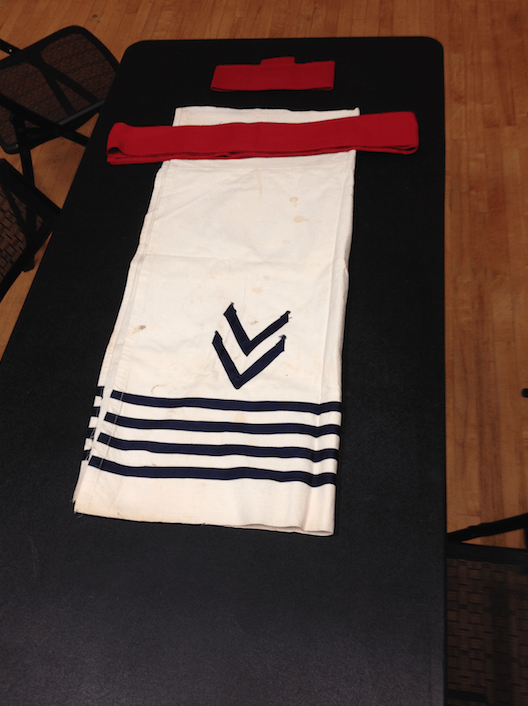

The Fitafita uniform is a distinctive piece of U.S. Navy and Samoan history. Unlike those who served in the 1st Samoan Marine Battalion during the Second World War, the Fitafita uniform had features of both Samoan culture and common U.S. Navy enlisted personnel. Most Fitafita wore a uniform that consisted of a red cap, white skivvy shirt, red sash, and white lava lava (a type of long dress kilt) with blue chevrons. The Fitafita occasionally wore an alternate blue lava lava dress uniform with red chevrons. The stripes sewn on the bottom of the lava lava kilt denoted rank. Personnel did not wear shoes.

“One of the Navy’s most unusual units is the Fita Fita Band, at U.S. Naval Station, Pago Pago, tutuila, American Samoa (All Hands Magazine, April 1949)

More opportunities came to native Samoans as the threat of war loomed over the Pacific. The Imperial Japanese co-prosperity sphere directly threatened the island’s stability. The importance of American Samoa grew critical in the early 1940s. Navy leadership accelerated the rapid growth of industrialization felt in the 1920s and 1930s. Plans for expansion of Naval Station Tutuila began in late 1940. In the event of war, Pago Pago would become a forward facility for the U.S. Navy and U.S. Marine Corps. American Samoa and the Fitafita were ready.

World War II

The attack at Pearl Harbor in December 1941 put all islands in the area on full alert, including American Samoa. The sleepy naval station soon became a major base of operation. Tutuila was the only armed base in the South Pacific at the outset of hostilities. It was also deemed important for its strategic location near the important sea-lanes between Hawaii and New Zealand. Several ships were directly diverted to Pago Pago after the attack. Confrontation with the Japanese at Tutuila seemed eminent. One month after Pearl Harbor, a Japanese submarine surfaced off Fagasa and fired rounds onto the island. The submarine attempted to strike the valuable fuel tanks in the village of Utulei. Only a U.S. Navy radioman and Fitafita guardsman were injured in the attacks. It would be the last hostile shots fired at the island.

The naval buildup in Pago Pago continued to increase during the war. According to one eyewitness account during the war, ships increased from “three in December, 1941 to fifty-six in December, 1942.” By October 1942, there were nearly 15,000 American servicemen on Tutuila and nearby Upolo. The Fitafita became an essential part of home defense and were instructed to “take the enemy forces under fire” in the event that another Japanese incursion.

Other Samoans put to work for food production, a vital component in fueling the war effort against Japan. The continuous flow of sailors and Marines made the island’s rich natural resources a necessity. Many Samoans worked long and restless hours to fulfill the needs of the fleet.

Plans to invade Samoa by the Japanese tapered off by the end of 1942. The pivotal battle of Midway in June erased any hope for a concerted Japanese offensive in the region. The Fitafita continued to drill and perform their duties, always ready to defend their South Pacific hamlet. By 1944, the base at Pago Pago was downgraded back to a naval station. Activities remained quiet until the end of the war.

The importance of the islands as a base of military operations waned after 1945. The U.S. naval base in Samoa officially closed in 1951. The last naval transport, General R. L. Howe, left the island on 25 June carrying many of the disbanded Fitafita guard to Hawaii. The territory was transferred to the Department of the Interior that year, as it remains today.

Samoans looked for economic opportunities both on and off the island chain. Recognizing the rapid growth of wage-labor opportunities brought on by war, many migrated to Pago Pago, its territorial capital. Others went to Hawaii and mainland United States. Yet the heart and soul of the Samoan people remains in Tuitula. It was there that a small and elite group of Pacific Islanders proudly served in defense of American freedoms and ideals.

As of 23 March 2009, twelve American Samoans have given their lives in defense of the United States. Many more proudly risk their own lives in the U.S. Navy. Today, the Navy estimates that sailors of Asian and Pacific Islander heritage comprise approximately 6.5 percent of the active duty naval force. That number includes over 20,000 active duty sailors, 4,000 reservists, and 18,900 civilian employees.

Preserving a Legacy

The Naval Historical Foundation seeks to preserve the history and heritage of the Fitafita warriors for future generations to learn and enjoy.

We hope that the uniform and exhibit will help to preserve the unique cultural bond between American Samoa and the United States Navy.

For information regarding the Fitafita uniform case and donation opportunities, please contact the author at [email protected] or by calling (202) 678-4333 ext. 6.

poker online terpercaya