Cracking Gibraltar is a blog series from the Naval Historical Foundation that will discuss the Army-Navy relationship involved in taking Fort Fisher, the last remaining Confederate stronghold in the Atlantic. READ PART I and PARTII.

PART III: Cracking Gibraltar

Following the embarrassing show of force at Fort Fisher in December, General Grant and other wartime leaders wanted to make sure the next effort against the vital coastal fortification would be the last. General Butler’s replacement for the Expeditionary Corps was Major General Alfred H. Terry, a career man who saw action at Bull Run and Petersburg. Grant and Porter wanted an officer who was not afraid to fight. General Terry more than earned that reputation in January 1865. It is that reputation that helped him later in life battling Indians and Custer’s ego during the Great Sioux War.

General Terry knew the profound importance of joint Army/Navy operations, having fought alongside Admiral Dahlgren’s forces at Charleston Harbor in 1863. General Grant wanted as little mistakes as possible so late in the war. He advised both expedition leaders to consult “freely” with one another in the days leading up to the attack. He hoped the open lines of communication between the two might right the wrongs of Porter and Butler’s toxic relationship. If they hoped to crack Gibraltar, they needed a plan as solid as its execution.

The total Union force heading back to Fort Fisher was comprised of 59 ships from Porter’s squadron and approximately 8,000 of Terry’s soldiers in four divisions.

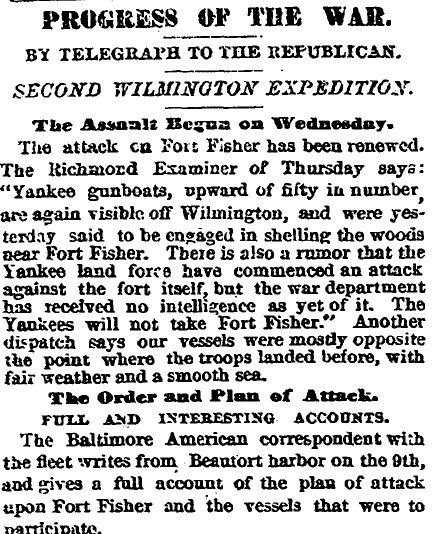

Colonel Lamb and his Confederates guarding Fort Fisher were not at all surprised by the upcoming attack. As early as the evening of 12 January, the small number of soldiers guarding the garrison could see the mass of ships and transports near the beach to their north.

Terry landed his troops north of the Fort as planned on 13 January 1865. Behind the strength of Terry’s force was over six hundred of Porters guns pointed straight at Fort Fisher. If the Civil War is to be condensed into a numbers game, Fort Fisher ranks near the top for its show of force.

The Union Navy began to bombard Fort Fisher that day. The shelling acted as a screen for Terry, who began to offload and prepare to assault from the north. The paralleled firing position allowed for the close-in fire needed to shell the fort to not interfere with the landings. Army transports landed in two separate groups, with one landing several miles to the north in case the need came to repel any Confederate reinforcements from nearby Wilmington. To say that the execution was textbook might be an understatement.

Another day of shelling rocked the Fort on 14 January. The rigorous shelling lasted the entire day and inflicted some 300 Confederate casualties from inside the fort. With less than 2,000 Confederates inside before the battle began, Colonel Lamb was at a severe disadvantage. Most important, the barrage took out some of the heavy guns. Everything was set for an assault the following day.

Union vessels began shelling the fort once again around 9:00am on 15 January. Confederate General Hoke was able to get several hundred soldiers into the fort during the three-hour bombardment.

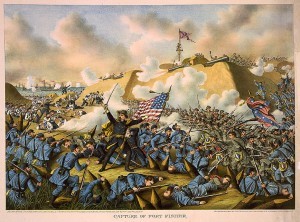

Porter sent a small contingent of sailors and marines on shore to aid in the assault. Unlike Terry’s forces, those who comprised the 1,600 man naval landing party had only cutlasses and revolvers to defend themselves with. The approximately 400 Marines going ashore had only rifles. Commander Kidder P. Breese was in overall command of the naval detachment. Breese was a close personal friend of Porter, who had been with him since the beginning of the war. It would take much more than cutlasses and revolvers to protect them as they organized into companies on the morning of 15 January. The Army originally planned for the naval landing party to attack in a series of waves, with the Marines providing covering fire.

Things did not go as planned for Commander Breese. The soldiers planned to attack simultaneously with the landing party were delayed, as they had to attack through the nearby woods. The sailors and Marines lumbered forward together in a mass of confusion and death towards the fort. Admiral Porter wrote about Commander Breese’s difficulties in his official report to Secretary Welles:“Lieutenant-Commander Breese did all that he could to rally his men, and made two or three unsuccessful attempts to regain the parapet, but the marines hving failed in their duty to support the gallant officers and sailors who took the lead, he had to retire to a place of safety. He did not, however, leave the ground, but remained under the parapet in a rifle pit using a musket until night favored his escape [. . .] Nowhere in the annals of war have officers and sailors undertaken so desperate a service.”

Casualties mounted up as they moved across the open beach. The sailors barely made it to the fort before they had to turn back in panic. Only a handful made it to the outer palisades. Many injured were unfortunately left for dead. One source recorded nearly a fifth of the sailors and Marines that charged that early afternoon became casualties.

Colonel Lamb, seeing the intensity of attack, believed the landing party to be the central attack column. General Terry’s men soon charged at the fort with a ferocity and embattled courage rarely seen in combat. The artillery fire from the defenders was once again fierce and concentrated, this time on Terry’s men. Thanks to Porter’s rolling bombardment from the water, the advancing infantrymen had a protective blanket of cover during their rush. Terry and his men who made it to the fort began the arduous process of fighting through towards the heart of the base through the long parapet. By 9:00pm, Fort Fisher was in the hands of the United States.

The victory came at the loss of over one thousand killed or wounded. Southern casualties totaled half of that number, with nearly 1,500 taken prisoner.

The capture of Fort Fisher closed the South’s last major port. Although there are some who would note that other ports still open until the end of the war (a true statement), the “lifeline of the Confederacy” nonetheless came to a near screeching halt on 15 January. With little opportunity for blockade runners to come into the mid-Atlantic South to aid Lee’s Army, it only was a matter of time before the end. The engagement did not force an end of the war; it merely accelerated its end.

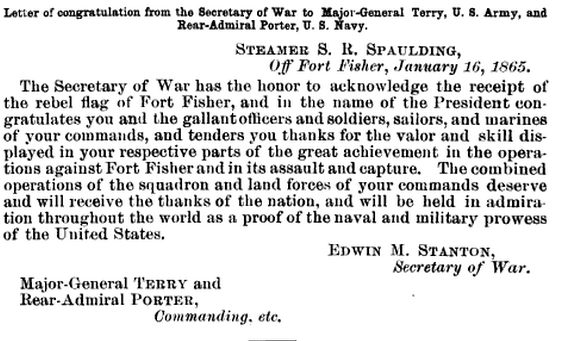

The New York Times ran on 19 January with a series of headlines covering the Union victory at Fort Fisher. The official report to the Secretary of War three days previous was equally positive. Note that both Porter and Terry wrote the report together – as equals:

The battle would be the last great victory for the Union Navy during the Civil War. For joint operations, many scholars point to Fort Fisher as a critical benchmark for cooperation and a solid framework for future operations in U.S. military history. In all, Union forces captured 139 guns and the surrounding earthworks and fortifications.