Cracking Gibraltar is a blog series from the Naval Historical Foundation that will discuss the Army-Navy relationship involved in taking Fort Fisher, the last remaining Confederate stronghold in the Atlantic.

PART I: The Jonah of the Fleet

President Abraham Lincoln awoke on the morning of December 27th to disheartening news. Less than a week after General Sherman presented him with the city of Savannah, Georgia, Lincoln opened a Richmond newspaper and read about the Army-Navy blunder at Fort Fisher. News traveled fast, and with great effect. The Confederacy seemed somehow resilient in light of recent events. The war was at a critical stalemate in Virginia and much of the southern coastline was clutched in the palm of the Union Army. Yet this crudely made soil and sand fort stood up to the Federal gauntlet. General Ulysses S. Grant called the entire engagement was a “gross and culpable failure.” He was right.

The offensive proved an embarrassing defeat – one of the worst suffered by the Union during the war. In reality, they beat themselves; the Confederacy was a shadow opponent. The results seemed out of the ordinary given the history of combined operation success in the western theater. Union forces failed to capture the South’s last remaining Atlantic port in a confusing spectacle of misinformation, missed signals, and poor management. Sixty ships and over 10,000 shells could not force the will of the Confederacy. The most unfortunate event during the holiday engagement was the fleet’s unsuccessful detonation of a disguised blockade runner (USS Louisiana) filled with explosives. Although General Grant and Gideon Welles doubted the offense would work, the attack strategy went forward on 23 December. Not unlike the entire attack itself, its explosion detonated without incident nearly a mile away from the fort. Soldiers at Fort Fisher got a fancy firework display as the kickoff to the attack.

Fort Fisher, N.C. Interior view of southeast end, showing site of main magazine (LOC Image: LC-DIG-cwpb-03673)

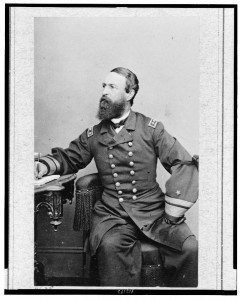

Although Rear Admiral David Dixon Porter Porter felt the fort was all but abandoned and demolished from the bombardment, General Butler had a different feeling from the ground – or so one would assume. Butler did not attend the assault himself. Even so, both leaders failed to communicate with one another. This was especially embarrassing for Porter. The battle smacked against his official role as the commander of the North Atlantic Blockading Squadron. Porter was furious. He took to pen and paper with an eagerness and ferocity as matched his fighting spirit in the days following the attack.

On the same day President Lincoln read the disheartening news in the paper, Porter wrote to Secretary Welles from the flagship Malvern about the myriad misgivings of his Army counterpart. “My dispatch [. . .] will scarcely give you an idea of my disappointment at the conduct of the army authorities,” Porter wrote in the opening salvo of his telegram. He was more than certain that the accuracy of Union gunfire silenced the guns at fort Fisher. In reality, there were more Confederates inside the fort than originally believed by Porter, yet far less than Butler imagined. He conveyed the extreme level of Butler’s unprofessionalism and insubordination in a series of weighty passages:

“Had the army made a show of surrounding it (the forts), it would have been ours, but nothing of the kind was done. The men landed, reconnoitered, and hearing that the enemy were massing troops somewhere, the order was given to reembark”

“To show that the rebels have no force here, these men have been on shore two days without being molested [. . .] I can’t conceive what the army expected when they came here; it certainly did not need 7,000 to garrison Fort Fisher; it only required to garrison all these forts.” (Porter to Welles, ORN, Series I, Volume II, 261-262)

Porter suggested that the makeup of the fort essentially “invited soldiers to walk in” and take possession. He ended the note with a few sharp concluding remarks and gave a positive outlook on a second follow-up engagement. He cited the discovery of the forts “weaknesses” from the December bombardment as a major factor in the future assault’s success. Despite the poor outcome initially, Porter believed a second chance under new Army leadership would be smoother. He threw support at General Winfield Scott Hancock, the hero of Gettysburg, as a possible candidate. Surely, he would not back down from the fight like Butler.

The Massachusetts Springfield Republican included several consolidated reports from Navy and government officials in their 2 January edition of the newspaper. Once again, blame pointed directly on Butler for the poor showing in North Carolina:

“In the fleet Gen. Butler is universally blamed, in vehement and emphatic terms,, for continual delays when the expedition was preparing, and for lack of enterprise when the action was in progress [. . .] a bold dash would have effected the capture of the place, almost without resistance.” (Springfield Republic, January 2, 1865, 2)

The article ended with a small passage summarizing Confederate reports of the engagement. The section’s title clearly indicated the military and public feeling towards Butler and his disappointing show at Wilmington:

Butler the Jonah of the Fleet

Butler fought war like a politician. Porter saw battles with the same scope and breadth of his father. The latter was needed to take Fort Fisher. The upcoming engagement would not be an easy ride for the Union Army and Navy as Porter had suspected. They could not simply “walk right in” the fort. There would be casualties this time.

Coming Soon – Part II: Butler’s “Singular and Interesting Disclosures:” The Rivalry Continues

Pingback: Cracking Gibraltar: The Union Takes Fort Fisher (PART II) | Naval Historical Foundation

Pingback: Cracking Gibraltar: The Union Takes Fort Fisher (PART III) | Naval Historical Foundation