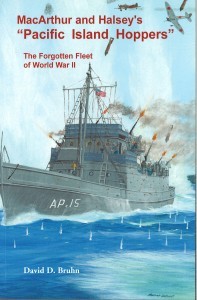

By David D. Bruhn, Heritage Books, Inc., Berwyn Heights, MD (2014)

By David D. Bruhn, Heritage Books, Inc., Berwyn Heights, MD (2014)

Reviewed By Christopher B. Havern

Through well-executed strikes by its land and naval forces, the Japanese Empire conquered vast stretches of Southeast Asia, the Southwest Pacific, and the Central Pacific in the six months after the attack on Pearl Harbor. In the process they built an extensive defensive perimeter. If Japan were to be defeated, that perimeter would have to be reduced through an arduous amphibious campaign. While the exploits of the marines and soldiers who landed on the hostile shores are generally well-known, the amphibious vessels and craft which put them ashore are less so. Even more unknown is the story of those unheralded vessels that transported the vital supplies that logistically sustained these landings that defeated Japan. David D. Bruhn’s book MacArthur and Halsey’s “Pacific Island Hoppers”: The Forgotten Fleet of World War II fills that gap in our understanding of the Pacific War.

A U.S. Navy veteran of twenty-four years, Bruhn seemingly specializes in writing histories of lesser known and certainly under-appreciated classes of ships. In this particular volume he recounts the service of those supply vessels that plied the waters of the Southwest Pacific. It began with the “Catboat Flotilla” which MacArthur gathered upon his arrival in Australia from the Philippines. This ad hoc force of US-flagged, but Australian-manned emergency acquisitions, was eventually replaced by the Small Coastal Transports (APc), Freight Supply Ships (FS), Large Tugs (LT), Small Tugs (ST), Harbor Tugs (TP), and Coastal Tankers (Y) built once the fully mobilized US could construct them. It was these vessels which helped feed the effort that resulted in the US and its allies driving the Japanese back from the apogee of their success. Whereas in the summer of 1942 the Japanese threatened the supply-lines to Australia, three years later the Japanese were desperately fighting on Okinawa at the very doorstep of the Japanese Home Islands. It was these “Island Hoppers” that supported the multiple landings of the largely unknown campaign which liberated New Guinea and helped break the Bismarcks Barrier. Their support enabled MacArthur to return to the Philippines and the Allies to retake oil-rich Borneo. Along the way, many of the vessels earned battle stars in conventional engagements with Japanese aircraft, ships, and troops. As the war dragged on they were even subject to suicide attacks from the Japanese special air and naval squadrons.

The strength of the book is Bruhn’s recounting of the island hopping campaign and these logistics ships support of it. In order to tell their story he clearly conducted a good amount of primary research, citing war diaries, ship’s logbooks, etc. In doing so he helps to fill a gap in our knowledge regarding the conduct of the war in the Pacific Theater of Operations. Another strength of the book is the appendices which not only provide statistical data for each of the vessels in the different classes that saw service in World War II, but also acknowledgment of personal awards and those won by these vessels in subsequent conflicts. That having been said, Bruhn’s book is not without its issues. Foremost among these is the maps. While it is appreciated that the author attempted to include maps of the islands around which these operations were conducted, many of these are illegible. As such, they are of limited utility and detract from the book’s quality. Another problem is the editing. In multiple locations there are errors of grammar, agreement, or awkward sentence structure that might have been corrected with better editing. Also, there was a number of instances where there were jarring factual errors. The foremost of these is Bruhn’s mention of the Japanese having lost three, not four, aircraft carriers at the Battle of Midway (page 19). Lastly, in a volume in which the author clearly conducted primary research, it is a little disheartening that he also cites Wikipedia articles in his notes.

While Bruhn’s intent to educate the reader on these less well-known, but vital vessels and their service in World War II should be lauded as the contribution to the narrative of the Pacific War that it is, the book would have benefitted from better maps and a bit more editing. These, however, are not fatal flaws. In the event of a second printing, these shortcomings, it is hoped, would be corrected.

Christopher B. Havern is with the USCG Historian’s Office in Washington, DC.