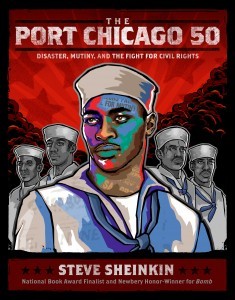

By Steve Sheinkin, Roaring Book Press, New York, NY (2014)

By Steve Sheinkin, Roaring Book Press, New York, NY (2014)

Review by: Aldona Sendzikas, Ph.D.

How do you explain racism to teenagers—specifically, the existence of institutionalized racism and segregation in the U.S. Navy during most of its history? This is author Steve Sheinkin’s challenge in this book for young adults about the massive explosion that killed 320 servicemen, most of them African American, at a California ammunition loading dock at Port Chicago in July 1944. It was a tragedy that drew attention to the Navy’s unfair treatment of black sailors.

As a former history textbook writer and the award-winning author of several history books for young adults, Sheinkin is experienced in broaching complex and difficult topics and making them accessible to young readers. Although the actual age of the intended audience is not stated in the book, according to YALSA (the Young Adult Library Services Association), the “Young Adult” category refers to readers between the ages of 12 and 18.

The Port Chicago 50 is well researched, carefully footnoted, and amply illustrated. Sheinkin’s sources include the 1,400-page transcript of the trial of the 50 black sailors charged with mutiny for refusing to work after the explosion. Sheinkin states that his objective was to tell the story of the Port Chicago events from the point of view of these young men—a perspective that is not considered in many accounts of the disaster. Sheinkin achieves his goal by incorporating excerpts from oral history interviews with several of the “Port Chicago 50.”

Sheinkin undertakes not only to narrate the events leading up to and following the Port Chicago explosion, but to unravel the social circumstances that shaped them: the history of racial segregation in the military and the slow road to its eventual end. Accordingly, Sheinkin provides context, beginning the book with a brief account of Dorie Miller in order to introduce the concept of racial segregation in the U.S. Navy during WWII. He then shifts smoothly to an examination of the history of blacks in the U.S. military, beginning with the Revolutionary War period. This short historical summary leads neatly back to WWII and the Port Chicago events, focusing on one particular African American sailor and how he ended up joining the Navy. Soon it is revealed that this is the sailor who would end up leading the Port Chicago “mutiny.”

Sheinkin looks at subtleties: he stops to consider reasons that politicians may have supported and maintained segregation in the armed forces through the years. He sometimes interjects in the middle of the text to emphasize a point and encourage his young readers to stop and reflect: “Think about that,” he will suddenly say.

This is the kind of book I am sure I would have enjoyed reading myself as a “young adult” – a riveting story that would also make me feel that I was learning something important as I read. In only 170 pages of text, Sheinkin provides a very thorough account. He describes the actual process of ammunition loading, as well as the daily routine of the men assigned to Port Chicago—details that are not included in most accounts of the explosion. Readers learn about Thurgood Marshall and his role in trying to vindicate the Port Chicago 50. The oral history excerpts sprinkled throughout the narrative offer a candid glimpse of the torn emotions experienced by these men whose patriotism was questioned because they spoke up about unsafe working conditions. Particularly interesting are the men’s reflections in later years about how the events of Port Chicago affected the rest of their lives.

Most importantly, the author does not talk down to his young readers. He pulls no punches in describing the damage caused by the explosion, noting that the vast majority of bodies were not left “whole enough to identify” (p. 67). He does not shy away from moral and ethical questions: was it right for the survivors to refuse to load any more ammunition because of the dangers, when other servicemen were also facing dangers and possible death on ships and in foxholes?What exactly constitutes a “mutiny,” anyhow? It should be noted that since the author incorporates direct quotes from the transcript of the trial, occasionally the term “mother—ers” appears, along with a note from the author explaining that the full word was spoken in the trial—but this is not a term that teenagers will not have heard before, and again, it shows that Sheinkin refuses to talk down to his audience.

Sheinkin demonstrates how the Port Chicago incident ties into the larger story of desegregation in the USN and in American society as a whole. He suggests that the Port Chicago 50 are just as important in the battle for civil rights in America as were Rosa Parks and Jackie Robinson. The real “crime” committed by the Port Chicago 50, he concludes, was not mutiny but rather drawing attention to the way the Navy treated African American sailors.

Dr. Sendzikas teaches at the University of Western Ontario, London, Ontario, Canada.