By Captain George Stewart, USN (RET)

This is the third in a series of articles by Captain Stewart detailing the technical specifications, manning, and operations of the U.S. Navy’s Fletcher class destroyers.

In my previous two articles (read Part 1 here, read Part 2 here) I gave technical and manning overviews of the U.S. Navy’s highly successful Fletcher class destroyer. This article describes destroyer operations as I remember them during the late 1950s. While some changes had taken place since 1945, most of the procedures were carryovers from World War II. In those days, the Navy had been heavily influenced by carrier task group operations during the war and the experiences with the Kamikazes during the Battle of Okinawa. My own ship, the USS Halsey Powell (DD 686) had been struck by a Kamikaze while escorting the carrier USS Hancock (CV 19) off Okinawa in 1945. There were 39 casualties and extensive damage in the after part of the ship. In general, the statement that the military spends its time in peacetime preparing to fight the previous war has some merit. Again, the terms “is” and “was” are used interchangeably in this article.

Destroyers have been called upon to perform a wide variety of duties. The days of surface to surface torpedo attacks had pretty well gone away, although we still retained that capability. But most of the other wartime functions still remained. Some that we were called upon to perform included:

- Acting as a member of a screen as part of a carrier task group against air, surface, and subsurface attack.

- Acting as a rescue destroyer (Plane Guard)

- Conducting anti-submarine operations.

- Acting as a radar picket.

- Controlling aircraft

- Shore bombardment (Practice only)

- Collecting intelligence (Formosa Patrol)

- Convoy Escort (Matsu & Quemoy in 1958)

There are probably some others that I have forgotten about.

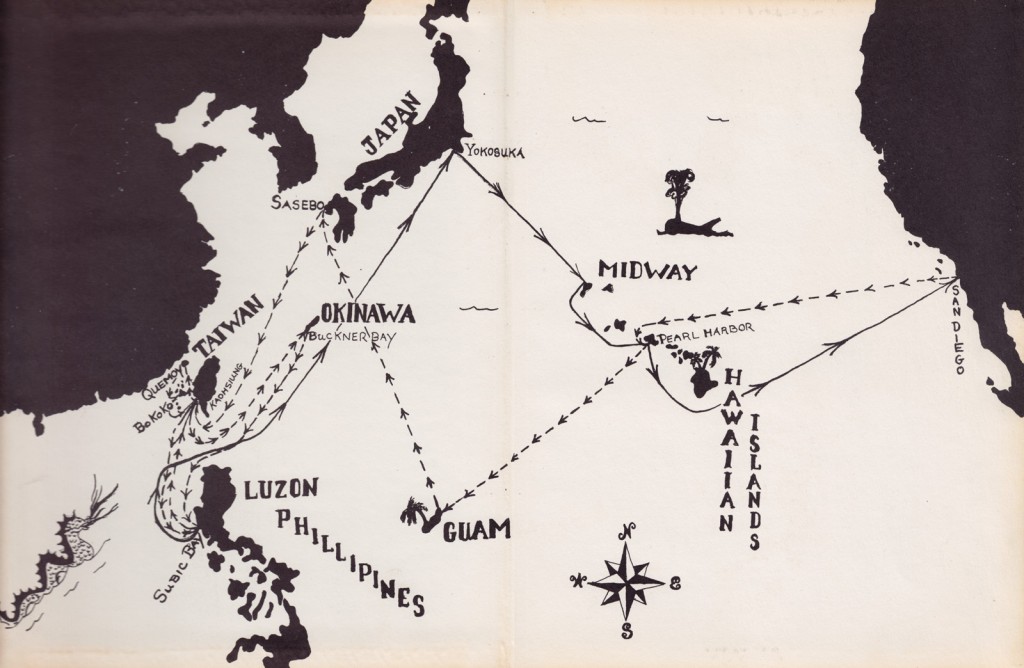

A Pacific Fleet destroyer operated on a two year cycle in those days. The cycle would start at the end of a shipyard overhaul, in our case at the Long Beach Naval Shipyard. This is how I met my wife. After the yard period there would be a stint at the Fleet Training Group in San Diego (Guantanemo for East Coast Ships) for refresher training followed by a work up for deployment to the Far East (WESTPAC). Deployments were six months in length followed by a six month period in the US, about half of which was spent underway in various fleet exercises off the West Coast. After two deployments, it was back to the shipyard again. I made six month WESTPAC deployments in 1957 and 1958.

Deployments to the Far East could be pretty tedious and they involved long periods at sea, as much as a month at a time. It seemed like there was always something going on out there in those days and port visits were few and far between. There was always a stop at Pearl Harbor on the way to and from the deployment for INCOP and OUTCHOP (Change of Operational Command) briefings at CINCPACFLEET. There were also fueling stops at Midway and sometimes Guam. The only ports we got to visit during my deployments were Yokosuka and Sasebo in Japan, Hong Kong, Kaoshung Taiwan, and Subic Bay in the Philippines. We also made fueling stops at Guam and Midway. East Coast deployments tended to be much better because ports in the Mediterranean are much closer together than in the Far East and there never were as many potential shooting situations over there that demanded that we be underway for prolonged periods.

Up until the 1960s, most naval home ports did not provide much in the line of pier space and in San Diego, we usually moored to a mooring buoy in the harbor. Normally all four ships in the division would be moored to the same buoy. Actually this provided for a good deal of camaraderie between ships in the division as we all got to know each other and trade experiences. While at the buoys we were provided with services with some harbor craft which were referred to as fuel, water, and garbage barges operated by the Naval District. Transportation was by a combination of ship’s boats and private water taxis.

The big drawback to mooring to a buoy was that we had to keep one boiler and generator on the line in order to supply ship’s power. About once per quarter we would be assigned an availability alongside a Destroyer Tender for routine repairs. The tenders could then supply us with power, thereby allowing us to shut down and go “Cold Iron”.

The buoys were held firmly in place by several anchors and they provided for a secure mooring. The first ship to moor had to place a boat in the water which carried the mooring party. The actual hookup was made by detaching one of the anchor chains from its anchor and passing it down to the mooring crew on the buoy, who would then connect it to a shackle. The ship had to approach very carefully directly into the current and hold itself in position during this process. The other ships in the division would then come alongside and tie up using regular mooring lines.

Navy ships never use this method any more, as sufficient pier space is provided in all of the navy’s home ports and all necessary services are provided from shore.

Next we will describe the process for getting underway from alongside another ship or a pier. Preparations would start several hours before getting underway, primarily down in the engineering spaces. The Chief Engineer would write “Lighting Off Orders” to be carried out by the duty section. Normally the crew stood duty on one day out of every three. Boilers had to be lit approximately 2 ½ hours before the scheduled underway time and about an hour would be required in each engine room to prepare the engines for operation. The goal was to have two boilers on line, one in each fire room, and have both engines ready for operation with the plant “split” (2 independent plant configuration) prior to setting what is referred to as the “Special Sea Detail”.

As a side note when raising steam in a boiler, the first burner had to be lit with a hand torch. The working part of the torch consisted of a rag wrapped around the end of the handle and secured by wire. The torch was kept in a small pot filled with diesel oil. The entire process of raising steam was started by making up a burner, igniting the torch with a match, inserting it into the furnace, and opening the fuel valve. Once the first burner was lit, subsequent burners could be lit from the adjacent burner. This method was still in general use in the Navy even into the 1990s and there are still some ships that still use it, even though burner management systems have been common on commercial ships since the 1970s. For this reason, all sailors of the Boiler Technician (BT) rating were meticulous about carrying a book of matches around with them at all times. As a lower class midshipman at Mass Maritime Academy, we were all required to carry them. My wife’s first comment when I took her around the ship for the first time was “You mean that you start all of this up with a match?”

On deck it was necessary to disconnect all shore services, pick up the ship’s boats, remove rat guards, and a variety of other actions, including preparing an anchor for dropping in an emergency.

At the time scheduled in the plan of the day, the boatswain’s pipe would whistle and the word would be passed “Now set the Special Sea and Anchor Detail’. This would be followed by “Now Set Material Condition Yoke Throughout the Ship” followed by “The Officer of the Deck is Shifting his Watch from the Quarterdeck to the Bridge”. Essentially what this meant was for the “first team” to take their assigned stations for getting underway. The CO, XO, Officer of the Deck (OOD), Junior Officer of the Deck (JOOD) and appropriate enlisted personnel would proceed to the bridge. The deck divisions would man the line handling stations with the First Lieutenant and Chief Boatswain’s Mate on the Forecastle and the Gunnery Officer in charge on the fantail. The engine room and fire room supervisors would man their stations. The Chief Engineer would be in the Forward Engine Room and the Main Propulsion Assistant would be in the After Engine Room. The Steering Gear room (“After Steering”) would be manned.

An explanation of Material Conditions is in order. A Naval vessel had three conditions of damage control readiness, X-RAY, YOKE, and ZEBRA. These conditions refer to degrees of closure to minimize the effects of potential damage. These conditions are established by closing the appropriate fittings such as valves, hatches, and watertight doors. The conditions are described as follows:

- X-RAY provides the least protection. It is set when a ship is in the harbor. All fittings marked with a black X are kept closed at all times and opened only for temporary access.

- YOKE is an intermediate level of protection that is set when the ship is under normal underway cruise conditions. All fittings with a black Y are closed and only opened for protection.

- ZEBRA is the highest level of protection. It is set under battle conditions. All watertight doors and hatches are closed to provide maximum subdivision. Fittings marked with a Red Z, Black Y, and Black Z are all closed.

The OOD would then execute a “Getting Underway” check list. Communications would be established with all vital stations, steering gear, alarms, whistle and engine order telegraph tested, radar, sonar, and fathometer in operation, and compasses checked. The last step was to test out the main engines with steam. Once this was accomplished, the OOD would pass the order to “stand by to answer all bells” to the engine room and them report “ready to get underway” to the CO.

The Conning Officer could be the CO, XO, or OOD. Most CO’s rarely took the conn themselves but acted more as a teacher and overall safety observer. The duties of conning officer were rotated around. Regardless of who it was, it was very important for him to announce “I have the Conn” so that all bridge personnel would know who to take their orders from. The next order would be to “Take in the Brow”.

The next step depended on how we were moored. Destroyers were normally tied up to a pier with six mooring lines, numbered consecutively from forward to aft. For a secure moor, the lines were “Doubled Up”. This meant passing a second bight around the bollard on the pier or the ship alongside. So the next order was “Single up all lines”. From there we were ready to go.

The conning officer would then use an appropriate combination of rudder, engines, and lines to get the ship underway. As soon as the last line was taken in, the boatswain’s pipe would sound and the announcement would be made “Underway, Shift Colors”. If we were backing out of a slip you would hear a prolonged blast on the whistle. At this point, we were underway.

While in restricted waters, naval vessels have a navigation detail set and the ships position was regularly determined by taking visual bearings on objects ashore, supplemented by radar ranges and fathometer readings. The navigator would be responsible for ensuring that the ship remained on its desired track and making appropriate recommendations to the CO/OOD. Pilots were only used when absolutely necessary in a strange port and most maneuvers were accomplished without tug assistance. In those days there was no bridge to bridge radio. They did not appear until the 1970s. All Rules of the Road situations were handled by whistle signals.

Once clear of the harbor, the navigator would announce that we were entering International Waters, where different Rules of the Road apply. At this point, the word would be passed “Secure the Special Sea and Anchor Detail, Set the Regular Underway Watch”. During World War II, the Atlantic Coast destroyers would probably be at battle stations with Material Condition Zebra set by the time that they cleared the submarine net.

Since 1975 all new destroyer, cruiser, and frigate types have been powered by aircraft derivative gas turbine engines. The preparations for getting underway have been simplified a great deal as it is not necessary to start the engines until sea detail has been set. The plant has to be started up from the Central Control Station below decks, but once it is ready for operation throttle control can be transferred to the bridge. A lot more information is available on the bridge from GPS, Electronic Chart Displays (ECDIS), etc. But with these exceptions, the basic procedures for getting a destroyer underway have not changed a great deal from what I have described.

Underway operations will be described in the next section. (read it here)

George W. Stewart is a retired US Navy Captain. He is a 1956 graduate of the Massachusetts Maritime Academy. During his 30 year naval career he held two ship commands and served a total of 8 years on naval material inspection boards, during which he conducted trials and inspections aboard over 200 naval vessels. Since his retirement from active naval service in 1986 he has been employed in the ship design industry where he has specialized in the development of concept designs of propulsion and powering systems, some of which have entered active service. He currently holds the title of Chief Marine Engineer at Marine Design Dynamics.

Pingback: Manning Fletcher Class Destroyers | Naval Historical Foundation

Pingback: Fletcher Class Destroyer Operations - Part II | Naval Historical Foundation

Michael Bell

John I. Parichuk

David Fogg

Pingback: The George Stewart I Knew | Naval Historical Foundation

Harvey J. Shaw, CWO4(SS),USN/RET

Benny Ezzell