By Norman Polmar

(Editor’s note: This is the eleventh in a series of blogs by Norman Polmar, author, analyst, and consultant specializing in the naval, aviation, and intelligence fields. Follow the full series here.)

I had the privilege of meeting Dr. Edward Teller, the “father” of the hydrogen bomb. Teller believed strongly that the United States should have had a demonstration of the atomic bomb for the Japanese leadership before the weapons were used to destroy Japanese cities.

We met on 14 November 1986. Earlier, as a member of the Secretary of the Navy’s Research Advisory Committee (NRAC), I had participated in a major study of theater nuclear war at sea. This background, coupled with my research and writing about the Soviet Navy, led me to write the article “The Soviet Navy: Nuclear War at Sea” in the July 1986 issue of the Naval Institute Proceedings, and, with Dr. Donald Kerr, the director of the Los Alamos National Laboratory, “Nuclear Torpedoes” in the August 1986 Proceedings.

These articles led to my being invited to speak at a small luncheon of nuclear weapons experts at the Department of Energy (DOE) to provide my views of a possible nuclear conflict at sea. The day before my talk I was asked if I would mind if Dr. Teller attended the session. Of course, I voiced no objection!

The session did not start well: We already were seated for lunch—15 DOE officials and I—when Teller walked in and took his seat opposite of mine. Looking at me, he asked, “Polmar… what kind of a name is that?” I explained its Russian-Ukraine origins. Then I asked, “Teller… what kind of name is that?” Not a good question.

The conversation never lagged at lunch and, as dessert was being served, I was asked to begin my talk. I was introduced and began speaking, using flip charts in that pre-PowerPoint era. At about my fourth or fifth chart, Teller stood and he began discussing the chart. After he spoke to that one and the next, he was politely asked to sit down and let me continue. The briefing went well with many good questions being asked, several by Teller.

I next spoke with Dr. Teller a decade later when we both were on a panel at the symposium “Crucible of Deliverance: Prisoners of War and the A-Bomb,” held in San Antonio, Texas. My close friend Thomas B. Allen and I had just published Codename Downfall (1995), and we were to speak on the need to employ the atomic bombs to end World War II. It was expected that Teller would explain why we should have first had a demonstration for the Japanese. Our session was immediately after lunch on 19 March 1995.

As we neared the time for our panel, I excused myself from my luncheon companions and entered the conference room to check out the panel seating arrangements. Teller was already sitting at the table, reviewing some papers. I reintroduced myself to Teller, who gave a vague acknowledgment that we had met before.

I said something along the lines of, “And, you plan to say that we should have had a demonstration before Hiroshima and Nagasaki?” He responded, “Why not?” I said that if I could have a couple of minutes—without his interrupting me—I could tell him why. This appeared to interest him. I began making my points, briefly and simply. Almost immediately he started to interrupt. I reminded him that I still had time left. He stopped.

The points that I outlined to Teller were—not necessarily in this order:

- U.S. and Japanese officials communicated through the Swiss Red Cross; “negotiations” for a demonstration would have been complex and time-consuming.

- Would the Japanese believe or trust the United States enough to risk sending scientist and military officers to a location of our choice?

- How would the Japanese observers be transported safely to the demonstration site during a fierce combat environment?

- Would the Japanese try to shoot down the B-29 bomber carrying the bomb to the demonstration site?

- Would the Japanese officials, observing the demonstration, believe that the massive detonation was caused by a single bomb—or by trickery, perhaps with previously planted explosives?

- Would the massive “water spout” caused by the detonation be realistically indicative of the potential damage to a Japanese city?

- What if the bomb did not work… it probably would be a gun-type plutonian bomb which, while simple in design, would not have been previously tested.

When I finished, he mumbled something along the lines of, “Interesting points, Polmar.”

The conference reconvened and Teller began his remarks. He started by mentioning the number of people with whom he had spoken at the conference who believed that the atomic bombing of Japan was necessary. Then, he declared, “For the first time, I had a very real impression of something that almost amounts to a complete moral justification of using the bomb.” The audience broke into applause.

Later in his remarks Teller did mention his idea that detonating a nuclear weapon 30,000 feet over Tokyo Bay—that would have been seen by ten million Japanese people—would have convinced the Emperor that surrender was necessary. But, one must ask, would an atomic bomb detonation at 30,000 feet over Tokyo Bay be seen as an indication of the bomb’s awesome destructive power? Or, would it appear to be merely a massive pyrotechnic display? Of course, the Japanese people had absolutely no influence on the six-man council that ruled Japan at that time.

After the session Teller said a few words to me, again indicating that my points for not having a demonstration of the atomic bomb had been “interesting.”

Stanley Falk

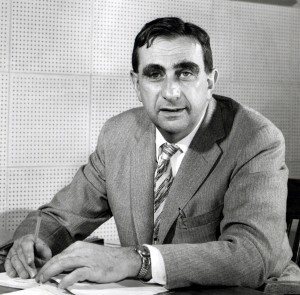

N Polmar

Pingback: : Edward Teller and the A-Bomb By Norman Polmar I had the privilege of meeting Dr. Edward Teller, the “father” of the hydrogen bomb. Teller believed strongly that the United States should have had a demonstration of the atomic bomb for the Japanese le