By Robert J.Moore and John A. Rodgaard; Holywell Publishing, St. Albans, Hertfordshire, UK, (2010).

By Robert J.Moore and John A. Rodgaard; Holywell Publishing, St. Albans, Hertfordshire, UK, (2010).

Reviewed by Thomas C. Hone, Ph.D.

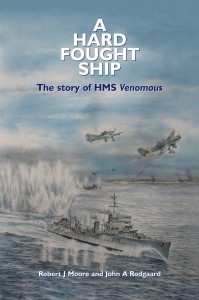

This well-illustrated paperback book covers the career of a Royal Navy destroyer commissioned in 1919 and the experiences of the men who served in her. The book does a splendid job of giving the reader a sense of what it was like to serve on a small, long-serving destroyer. Most such “you are there” books place the reader on a ship during one campaign or one engagement. A Hard Fought Ship covers the lifetime of Venomous, a ship that was neither famous nor glamorous. This is important; most sailors who spent much time at sea in World Wars I and II did so on ships whose names most of us do not know. Without books such as A Hard Fought Ship, their every-day reality would be lost to us.

This edition is a revision of an earlier manuscript compiled by Robert J. More, a former commanding officer of the Royal Navy Sea Cadet detachment named for the ship. LCDR Moore died suddenly at age 63, and his friend, retired US Navy Captain John Rodgaard, added new material and shepherded the manuscript in its final form to publication. I doubt the book would have been as faithful to naval life as it is without the great endeavors and naval experience of these two authors.

Venomous was not a big ship—1,100 tons displacement, 300 feet long, 29 feet broad at her widest point, and originally drawing about 11 feet. But when new, her 27,000 shaft horse power turbines could drive her through the water at 34 knots, and she was originally armed with four 4.7 guns, one 12-pounder, and two sets of three 21-inch torpedo tubes. She had been designed to screen a concentrated force of battleships and, if required, to fight her way through an opposing screen to torpedo enemy battleships. In her long and busy career, that is not what she did. Instead, Venomous did almost all the other things that destroyers of her age and type did. She served as a scout, as an escort, as a gunfire support ship, as an anti-submarine unit, as a make-shift transport, as a life-saving ship, and even—at the end of her career—as a mobile target helping to train Royal Navy torpedo plane crews.

In short, her successive crews had to adapt to situations that had not been anticipated when Venomous was originally designed, and sometimes the members of her crew found themselves on missions that few had ever dreamed they would undertake. For example, over the winter of 1919-1920, the ship made several cruises into the Baltic Sea, where she participated in halting a German force (yes, a German force under Major General Adolf Goltz) invading Latvia and served to deter Bolshevik naval assaults on Estonia and Finland. All this with a crew many of whose members thought the “war to end all wars” was over. And, as if that weren’t enough, Venomous and her crew found themselves trying to keep gun-runners out of Ireland in 1920 and a major coal mine strike from paralyzing the British economy.

In 1923, Venomous shipped out for the Mediterranean, where she was to operate out of Malta until 1929. But in 1923, there was time to get involved with Greek-Turkish violence and modern Turkey’s struggle for independence and recognition. It’s easy now to forget how much violence there was in Europe and the Middle East after World War I had ended. Venomous and her crew were caught up in some of that; the Eastern Mediterranean and the Aegean in the early 1920s were not calm, settled places. But once Turkish-Greek violence had abated, Venomous began a long association with the carrier Eagle and battleships of Britain’s Mediterranean squadron. In 1929, however, the ship was placed in mothballs at Rosyth, to be brought back into service (though temporarily) during the war scare in early October 1938.

Once the war scare abated, Venomous returned to the reserve fleet, only to be recalled again in the summer of 1939. The destroyer was old and carried a meager antiaircraft armament of two machine guns and two 2-pounder pom-poms, prompting one sailor to react to his assignment to Venomous by saying, “This is an old tub.” Old tub or not, the destroyer escorted convoys of British troops to France, screened coastal British shipping against German naval units, landed British troops at the Hook of Holland—and then took them off again as German troops approached. Venomous, like so many of her sisters, was a star at the end of May and the beginning of June, shuttling day after day from Dover to the French coast—taking British troops to France (Boulogne, for example) and then taking them off again, pulling refugees out of Calais, and then heroically evacuating soldiers from Dinkirk. The small ship was bombed and strafed, turned her 4.7-inch guns on German forces trying to trap her in Boulogne’s harbor, and her crew had over and over again to find places for evacuees. Sometimes Venomous had so many soldiers aboard that she was in danger of losing her stability. Yet she carried on, performing an essential naval mission—saving her country’s army.

After Dunkirk, Venomous was given a 3-inch antiaircraft gun in place of one set of torpedo tubes, and the ship participated in anti-invasion patrols, protected coastal shipping against German E-Boats, and escorted British minesweepers, which were constantly on the lookout for mines dropped by German aircraft. Then it was back to the Mediterranean in the fall, and then back again to convoy escort duty in the Atlantic. Damage from a mine explosion sent Venomous in for repairs, and she emerged in 1941 with a radar set and without one 4.7-inch gun—taken off to increase space aft for lengthened depth charge racks. More duty as a convoy escort in the Atlantic was followed by another spell in a dockyard to tend to her cranky boilers in August 1941, and in November Venomous collided with another destroyer and was seriously damaged.

After major repairs, Venomous was down to just two 4.7-inch guns, but she had gained an anti-submarine Hedgehog and—finally—a new, improved radar. She was off to Russia with another convoy in April 1942 and steamed back to Londonderry in June. Then she was dispatched to the Mediterranean, where she participated in Operation Pedestal (the relief of Malta) in August. That operation has been covered in Peter Smith’s Pedestal, the Convoy that Saved Malta, and Moore and Rodgaard leave the details to Smith’s account, but again you see the Royal Navy drawing on all its ships—even the really old ones—to sustain the Allied campaign in North Africa. That fall, more boiler trouble sent Venomous back to England for repairs, and she emerged just in time to participate in Operation Torch, the invasion of North Africa. The authors spend a whole chapter on the unsuccessful effort by Venomous and two other escorts to save the depot ship Hecla from a U-boat attack the night of 11-12 November 1942, and the vivid story is a brutal reminder of just how difficult it was to fend off a determined German submarine commander intent on his target.

After refueling in Casablanca, Venomous ferried Hecla’s survivors to Gibraltar, and then the destroyer went back to work off the North African coast, eventually participating in Operation Husky (the invasion of Sicily) before being sent back to England for boiler and engine room repair.

Venomous had more adventures, including steaming to Norway to help take supplies required by British teams there to supervise the surrender of German forces in 1945. But I think this incredible but not unusual operational history can give the reader a good idea of what ships and crews went through in the long sea war in Europe from the fall of 1939 to the late spring of 1945. What makes A Hard Fought Ship of value is the way that the authors blend the story of the ship’s operations with the memories and accounts provided then or later by the ship’s crewmembers. People came and went in Venomous throughout her long career. Hardly anyone on her in 1945 had served on her or on one of her sisters in 1939. But all these officers and enlisted personnel carried on—working, sweating, shivering, tolerating cramped living conditions and the sometimes awful smells of their often unwashed fellows, and enduring attacks by the enemy. In reading A Hard Fought Ship, I was reminded of similar stories from the histories of the U.S. Navy’s “four-stack” destroyers in World War II: old ships with young men, many of the latter with no previous experience at sea.

A Hard Fought Ship tells us what it was like in a mobilized navy with its back to the wall. We already have a fictional account of that navy in the wonderfully written The Cruel Sea, by Nicolas Monsarrat. Authors Moore and Rodgaard have now given us a factual, well written, and well-illustrated account. For those readers less familiar with destroyers and how they operate, we must thank Moore and Rodgaard for also providing the reader with very useful appendices on shipboard organization and routine life aboard Venomous. These appendices, and others, are the icing on a very edible “cake” of a book.

Dr. Hone has recently published a book The Battle of Midway with the Naval Institute Press.

Thomas J. Brown, Naval Order of United States, Charleston Commandary