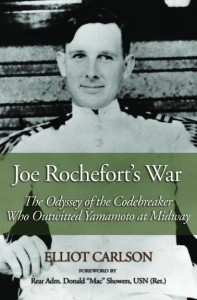

By Elliot Carlson, Naval Institute Press, Annapolis, MD (2011).

By Elliot Carlson, Naval Institute Press, Annapolis, MD (2011).

Reviewed by Capt. John A. Rodgaard USN (Ret.)

Joe Rochefort is a legend to all United States Navy intelligence professionals and Elliot Carlson’s outstanding biography finally introduces the man behind the legend. The author also lifts the veil of mythology and mystery that has surrounded the head of Station Hypo, the U.S. Navy’s signals intelligence unit at Pearl Harbor during the early days of America’s involvement in World War II.

The author brings Rochefort to life, from his days as one of seven children born of an Irish father and a Canadian-Irish mother, living in Southern California, to the officer in charge of Station Hypo and his post Hypo Navy service. His parents had high hopes for all of their seven children, “…especially for Joe. They wanted him to become a priest”. But, Joe went his own way.

Coming up through the enlisted ranks, a rarity within the officer corps at the time, this mustang’s talent was recognized early as nothing less than brilliant. Through his junior officer years afloat and ashore, Rochefort never failed to impress his seniors, especially such senior officers as Admiral Joseph Reeves, Commander in Chief of the U.S. Fleet and the Father of the Navy’s carrier aviation. However, Rochefort’s personality possessed a broad independent streak that often expressed itself sardonically toward those senior officers whom he considered foolish and or inept. Carlson’s treatment toward Rochefort is sympathetic, but he clearly recognizes the “feisty” nature in his subject’s personality.

However, as the author shows, Rochefort did find a kindred spirit in another junior officer. They formed a lifelong friendship starting with the years they spent in Japan, learning the language and understanding the country’s culture. The friendship between William Layton and Joe Rochefort would change the course of history. In this instance, it would change the course of the Pacific War.

The author weaves Rochefort’s story within the framework of Navy operations and organization during the interwar years. Carlson shines a glaring light on how things really were, especially pertaining to the intense, ugly political rivalry between the Office of Naval Communication and the Office of Naval Intelligence – a rivalry that Rochefort found himself in the middle of more times than none.

It is one of the author’s many achievements that he describes how things really got done within the culture of the naval officer corps and how that culture affected Rochefort. As a mustang, Rochefort was not a naval academy man and as such, it “deprived him of the coterie of friends and the professional network that inevitably follow four years at Annapolis, resulting in a bias that followed him throughout his career.” Carlson’s biography is as much a story of Rochefort’s struggle with the Japanese code as with the Navy’s officer corps and the heartless bureaucracy that the Navy can be to its “misfits.”

Those who are familiar with the events leading up to Pearl Harbor as well as those occurring six months later will share Rochefort’s exasperation as he and his small team search in vain to determine Yamamoto’s Kido Butai’s (Carrier Force) ultimate objective. Then again, you share his triumph in successfully tracking the operations of the Japanese that leads to the strategic success at the Battle of the Coral Sea and the breaking of the code that leads to the accurate forecast that Midway is the objective for the vaunted Kido Butai and its invasion force. However, Station Hypo and its analyses was intensely resented by members of the naval staff in Washington, and the course that Rochefort took in correctly assessing Japanese intent led to his removal as Station Hypo’s OIC and the denial to him of the Distinguished Service Medal that was recommended by Admiral Nimitz. It would take over 40 years for the wrong to be corrected.

This aspect of Rochefort’s career, despite his own prolific ability to create enemies in high places, is still an object lesson for those intelligence professionals. Carlson reveals that the business of intelligence is after all a human endeavor, and as such, it is one that can be fraught with power games and bitter rivalries, which can be detrimental to the welfare of the nation.

However, the author is demonstrative in showing how Rochefort’s superior analytic skills and his exhausting tenacity set the groundwork for victory. As one who was taught that intelligence drives operations, strategy and tactics, I find that Elliot Carlson’s work establishes Joseph Rochefort as the model for 21st century intelligence analysts to emulate. I am confident that his book will become mandatory reading for all sea service intelligence professionals.

Captain Rodgaard is the co-author of “A Hard Fought Ship: the Story of HMS Venomous.”

Pingback: The Hazards of Cryptology - Andrew Speno

Pingback: Yardley - Andrew Speno

Pingback: Hero or Goat? - Andrew Speno

Pingback: Hero and Goat - Andrew Speno