The following speech was delivered by RADM Joseph F. Callo, USNR (Ret), to the Society of the War of 1812 in the State of New Jersey and Jamestowne Society at the Nassau Club of Princeton, New Jersey on 29 October 2011. It also appears in the Fall 2011/Winter 2012 issue of “Pull Together.”

The bicentennial of the War of 1812 is approaching, and after 200 years it’s time to change how we think about that war. To support that proposal, I’m going to explore what I believe the narrative of that war has been and how we might change it to make it more accurate and more relevant to our own lives and times.

In the past there have been heated—and mostly partisan—arguments about who won. Then in recent years, it became fashionable to claim that the war was a stalemate, with the further claim that it was simply a horribly stupid waste of life.

Those two latter conclusions are easy to slide into if one simply concentrates on the war’s military actions. For example, of 25 noteworthy naval actions, the U.S. Navy won thirteen and the Royal Navy won twelve. And along the Canadian borders there were bloody battles won and lost but no major change in the border. Then on the one hand the U.S. Navy won the critically important fleet actions on Lake Erie and Lake Champlain and American privateers had a significant effect on Britain’s vital sea lines of communication. But on the other hand, the Royal Navy was able to apply a punishing blockade and a series of successful expeditionary warfare raids against America’s Atlantic coast.

And so the discussions have rolled on. But while it’s true that there was no unconditional surrender by either side, and in a compilation of the results of individual actions there was no clear winner, there were indeed some very important, bottom line gains and losses for each side. And those gains and losses had long term, geopolitical implications for both the United States and Great Britain—and in fact for the world. But I’ll come back to that particular point towards the end of my remarks.

One of the biggest problems with the current narrative of the War of 1812 is, I believe, that there has been a tendency to focus on the main events as if they were free standing, rather than parts of a stream of interconnected campaigns, battles, policies, and decisions. And the corollary of seeing the War of 1812 as a series of free-standing events is that tactical matters inevitably overshadow strategic matters.

There is a very interesting new book out. Some of you may have read it already. The book’s title is 1812—The Navy’s War, written by George Daughan. Towards the end of the book there is, for me, a particularly enlightening passage. The passage quotes from a letter from the Duke of Wellington to the British prime minister at the time, Lord Liverpool. The prime minister had suggested that Wellington go to Canada and take over leadership of the land war along the Canada-U.S. border. At that point Wellington had a deserved reputation as a successful field commander in the Peninsula Campaign against Napoleons’ army. Wellington’s response focused on an important point. This is what he said:

“That which appears to me to be wanting in America is not a general, or a general officer and troops, but a naval superiority on the Lakes….The question is, whether we can obtain this naval superiority….If we cannot, I shall do you but little good in America.”[i]

Wellington understood the continuing strategic issues of the War of 1812, in this case the question of whether or not the British could take control of the communication and supply routes represented by the Great Lakes and Lake Champlain. Wellington wasn’t thinking tactically. He was confident that he could dominate in the field in most situations with his experienced troops. He was instead emphasizing the kind of strategic issue that gives context to individual actions and decisions.

And the importance of context is nowhere more important than when trying to establish the true causes of the War of 1812. The American declaration of war in June 1812 is generally attributed to America’s need to assure “free trade and sailors’ rights.”

In the book Sea Power—A Naval History edited by E.B. Potter and Admiral Chester Nimitz, the circumstances behind that battle cry are spelled out succinctly:

“In the post-Trafalgar period the intensifying commerce warfare between Britain and France left the United States the only major neutral trader on the high seas. American merchant shippers enjoyed unprecedented prosperity both in the general carrying trade and as exporters of American wheat, tobacco, and cotton. At the same time American merchantmen and even naval vessels, caught between Britain’s Orders in Council and Napoleon’s retaliatory Decrees were subjected to increasing interference that eventually grew intolerable.”[ii]

That’s fine as far as it goes, but in reality there was more—much more—to the story than a simple desire for free trade and sailors’ rights.

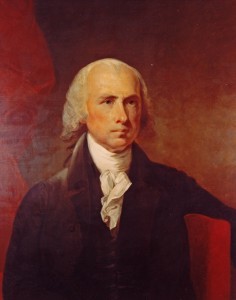

As the war approached, there were also strong, emotionally- laden political and diplomatic cross currents that shaped the decisions of President Madison and then-British Prime Minister Spencer Perceval. And politics, as we know, is often a force unto itself.

While Madison was the leader in the House of Representatives, he steadfastly resisted the pressure of those in Congress who were inclined towards war with Great Britain. Those advocating war were mostly from the South, along with expansionists from the then-western states of Kentucky, Tennessee, and Ohio, who were anxious to push the United States’ borders to the west.

Notwithstanding the pressures coming from those inclined towards war with Great Britain, Madison acted on his belief that he could avoid armed conflict by convincing Prime Minister Perceval that a major clash was inevitable, unless Britain dealt with the issues of free trade and impressment. Madison was further convinced that Great Britain’s preoccupation in Europe with Napoleon would make Britain reluctant to open up a new global warfront.

Madison was wrong on all of the above. In fact Perceval believed that the regional political divisions within the United States, along with America’s obvious military weakness would force America to accommodate Britain’s maritime policies, no matter how onerous or economically damaging. In addition Perceval and many around him believed that U.S. complaints could be quieted with a limited application of military pressure. All of the foregoing created perceptions on the part of the British leadership that were as important as the actual circumstances involved.

There was another important psychological factor among much of the British leadership. As a result Prime Minister Perceval and his successor, Lord Liverpool, who became Prime Minister in May 1812, had a desire to settle scores with the United States. In the first chapter of his book, Daughan is blunt:

“The Treaty of Paris…hardly reconciled the king or his people to colonial liberty. Bitter about their humiliating defeat, the British watched with satisfaction as the thirteen states floundered without a central government….Many in London expected the American experiment in republican government to fail.”[iii]

The Evening Star in London put things in more colorful terms:

“England shall not be driven from the proud pre-eminence, which the blood and treasure of her sons have attained for her among nations, by a piece of red, white, and blue striped bunting flying at the mastheads of a few fir-built frigates manned by a handful of bastards and outlaws.”[iv]

As we know the feelings were mutual, and it’s difficult to overemphasize the importance of sentiments such as those when discussing the reasons for the War. Yet they usually get little emphasis, if any.

The miscalculations on both sides that contributed to the U.S. declaration of war continued into the armed conflict. For example the British leadership failed to recognize the importance of the U.S. Navy’s early, morale-boosting, tactical victories in the early single-ship actions.

Those stunning single-ship actions were shrugged off at the Admiralty and Whitehall as embarrassing but basically non-determinants in the war, when they were in fact hugely important in sustaining a fighting spirit in the U.S. Navy. And of greater importance, those early naval victories sustained the will of the American political leadership and the public to fight on in the war.

The British were not alone in this pattern of miscalculations. For example the U.S. political leadership constantly misjudged the determination of most Canadians to remain part of the British Empire. A month into the war, then-former-president Jefferson, famously opined: “[T]he acquisition of Canada this year, as far as the neighborhood of Quebec, will be a mere matter of marching.”[v]

The serious misjudgments were still evident—not surprisingly at this point—during the peace negotiations that began at Ghent in August 1814. In the early phases of those deliberations, for example Madison doggedly believed that the British were anxious for a negotiated peace. When in truth Prime Minister Liverpool was convinced that with the pressures of Britain’s blockade and expeditionary warfare raids—particularly the presumably devastating psychological impact of the burning of Washington—the United States would not, could not, sustain the war for much longer.

So we see that the War of 1812 was launched and sustained to a significant degree by one false impression after another and a high degree of emotion on both sides. It wasn’t until the connected Battles of Lake Champlain and Plattsburg that the direction of the negotiations at Ghent finally changed. And at that point they changed radically.

With Commodore Macdonough’s victory over a British fleet on Lake Champlain on 11September 1814 and U.S. Brigadier General Alexander Macomb’s accompanying repulse of British General Prevost at Plattsburgh—along with the subsequent withdrawal of Prevost’s army to the north—the strategic nature of the War of 1812 was suddenly altered.

The Battle of Lake Champlain became the main tipping point by stopping a British thrust down Lake Champlain and the Hudson Valley and into the commercial heart of America. Such a campaign, if successful, would in all probability have shattered the United States geographically and ended the nation then and there. The coincidental repulse of the British attack on Baltimore was the exclamation point on the new strategic equation.

Let’s shift focus now to assess the outcome of the war. On the positive side for Britain, the period of relative peace that followed the war allowed Britain to benefit economically from her foreign trade and to firmly establish her de facto dominance of the seas. The latter would prove to be an unchallenged and immeasurable geostrategic benefit to Britain for a century. The end of the war also helped Britain to focus on the Industrial Revolution’s early stages and to quickly become the world’s largest economy. These were obviously important and very positive outcomes of the War of 1812 for Great Britain. It should be noted, however, that notwithstanding those positives, there were many in Britain who felt that their nation had conceded too much at Ghent.

On the positive side for the United States, the dominant position of America in Florida and Louisiana was confirmed and the possibility of a massive buffer Indian nation in the territories that would become Ohio, Indiana, and Michigan was eliminated. And U.S. foreign trade was once again able to contribute to America’s burgeoning economic might.

In addition and arguably most important of all, the United States gained international stature that did not exist before the war. The companion to that new stature was the recognition in the United States that a strong, standing military was an essential component of national security, and both the U.S. Army and U.S. Navy emerged from the War of 1812 as more professional military services.

Many—perhaps most—would agree that at the center of that new American global stature was the U.S. Navy, a force that had established emphatically that it not only would fight against the best, but it also could win decisively at that level. And it could win not only in a tactical context but in a strategic context as well.

Frequently the War of 1812 is referred to as America’s second war of independence, and it was that. It was also the validation of the implausible vision of John Paul Jones who wrote in 1778:

“Our Marine (Navy) will rise as if by enchantment and become, within the memory of persons now living, the wonder and envy of the world.” [vi]

Representative of the new U.S. Navy that was shaped during the War of 1812 was a group of officers referred to as “Preble’s Boys.” They were named for Commodore Edward Preble, who noted the youth of his officers when he was in command of a squadron in the Mediterranean during the Barbary Wars. All his captains were less than 30 years old—some were in their early 20s. After a few months of action in the Mediterranean, however, “Preble’s Boys” established themselves as exceptional warfighters, officers who were forward-leaning if not downright aggressive in their combat doctrines.

Among the “Preble’s Boy’s” who went on to distinguish themselves in the War of 1812 were William Bainbridge, victor in the action between USS Constitution and HMS Java; Stephen Decatur, who defeated HMS Macedonian while in command of USS United States; Isaac Hull, victor over HMS Guerriere while captain of USS Constitution; Thomas Macdonough, victor at the Battle of Lake Champlain; David Porter, who, as captain of USS Essex captured HMS Alert, the first British ship captured in the War of 1812; and Charles Stewart, who captured HMS Cyane and HMS Levant in a single extended action.

“Preble’s Boys” were part of the new breed of professionals who bridged the gap between the inward-looking and basically defensive attitudes that followed the American Revolution and the global sea power concepts that came to maturity at the beginning of the twentieth century with President Teddy Roosevelt and Admiral A. T. Mahan. In a book by Allan Westcott titled Mahan on Naval Warfare—Selections from the Writings of Rear Admiral Alfred T. Mahan, the Introduction includes the following:

“[T]he historian of sea power (Mahan) had much to do with the emergence of the United States in 1898 as a world power, with possessions and new interests in distant seas. And no one believed more sincerely than he that this would be good for the United States and the rest of the world.”[vii]

It was “Preble’s Boys,” along with those who fought with them and paid a heavy price in blood, who connected ideas of liberty with the steady progress of globalization that continues up to our own times.

In his book On Seas of Glory, former Secretary of the Navy John Lehman wrote at the beginning of his chapter on the War of 1812:

“Before the War of 1812 the young republic did not have an organized naval service in the truest sense. Gradually, the need to defend the commerce of the fragile new nation against warring European powers, Barbary pashas and pirates created the foundation of the U.S. Navy in fits and starts.”[viii]

At the end of the chapter Lehman’s focus is far reaching:

“The early efforts of Adams, Jones and Barry to establish institutional permanence were now accomplished, complete with a rich store of custom and tradition, borrowed liberally from the British and French navies, but very distinctly American….The new republic now had a formidable instrument to build a global commerce, enforce a Monroe Doctrine, and when the test came, to preserve the Union from rebellion.”[ix]

At the beginning of my remarks, I said there were a lot more than tactical victories and defeats during the War of 1812 and that there were very important gains and losses at the end of the war that had long term implications for both the United States and Great Britain—and in fact for the world.

To that point and in closing, I suggest that what the victories and defeats, mistakes on both sides, and the good and bad luck of the War of 1812 all added up to was a happening that is still playing out. That happening was the emergence of the United States as a global—eventually preeminent—naval power.

Our security and prosperity, as well as that of much of the world, is to a significant extent based on U.S. naval power, a global force that came forth in a brilliant flash of history between 1812 and 1814. It was a marriage of democratic political concepts to sea power. It was a phenomenon that harks back to Themistocles and the triremes of the Athenian empire of the fifth century BC.

The conjunction of American theories of liberty with global sea power in 1814 is, in my opinion, the single most important outcome of the War of 1812. And it was an enormously important—and mostly positive—outcome that has born heavily on world history. We ignore that message from history at great risk.

[i] 1812—The Navy’s War, George C. Daughan (New York, Basic Books, 2011), 356

[ii] Seapower—A Naval History, edited by E.B. Potter and Admiral Chester Nimitz (Englewood Cliffs, NJ, Prentice-Hall, Inc., 1960), 207

[iii] 1812—The Navy’s War, George C. Daughan (New York, Basic Books, 2011), 1, 2

[iv] The Perfect Wreck—“Old Ironsides and HMS Java—A Story of 1812 , Steven Maffeo (Tuscon, Fireship Press LLC, 2011), iii

[v] Perilous Fight—America’s Intrepid War with Britain on the High Seas, 1812-1815, Stephen Buduansky (New York and Toronto, Alfred A. Knoff, 2010), x

[vi] John Paul Jones: America’s First Sea Warrior, Joseph Callo (Annapolis, Naval Institute Press, 2006), 62

[vii] Mahan on Naval Warfare, Alan Westcott (Mineola, NY, Dover Publications, 1999), xviii, xix

[viii] On Seas of Glory, John Lehman (New York, The Free Press, 2010), 103

[ix] Ibid., 140, 141

Pingback: RADM Callo Speaks at Detroit Athletic Club on War of 1812 | Naval Historical Foundation

Robert F. Marvin M.D.

jamey