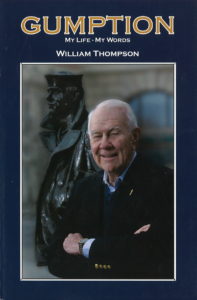

By Rear Adm. William Thompson, USN, (Ret.), Self-Published (2010)

By Rear Adm. William Thompson, USN, (Ret.), Self-Published (2010)

Reviewed by Cdr. Eric Dietrich-Berryman, USN (Ret.)

“Billy, you will never amount to anything unless you get some gumption and some business in your head,” Bill Thompson’s grandfather admonished the 13-year old boy.

But the old man had utterly failed to read the true measure of his grandson. William Thompson may not then have understood the word, but he had gumption to spare. Gumption cued his life from childhood all the way to becoming a naval flag officer. From patriarch of a thriving family to the realization of architectural dreams that changed the face of the nation’s capital on the Navy’s birthday in 1987 when the flag-draped rotunda of the U.S. Navy Memorial on Pennsylvania Avenue opened to the world.

In Escanaba, Michigan, on September 16, 1922, there seemed to be no time with either parent to decide on, and register, a middle name. William NMI [No Middle Initial] Thompson it was to be. It was short, to the point and coincidentally appropriate for his four-and-a-quarter pound birth weight. Appropriate, because by instinct, education, and training he made an art form of brevity.

It is the curse of many modern managers to reach for consensus decision-making. In military and corporative offices, this dodges personal responsibility and consumes inordinate amounts of time, besides. In high school, as a junior officer and up through the ranks to his last cruise as an honored guest aboard USS Nitze, Thompson always got to the point quickly. Details sorted themselves out in due course.

Gumption: My Life – My Words, first put to paper in 2010 and privately published in 2017, is a highly personal, very candid memoir. It tells the story of a man, true to himself and to the men and women (civilian as well as uniformed), who followed his calling.

This was not for fame or glory. He is an American Midwesterner through and through, who loved ships and the sea and discovered that he worked happily, cheerfully with men and women who shared the same convictions and vocation.

Gumption is an odyssey that begins with the boyhood experience of debilitating economic ruin during the Great Depression when the family lost its financial resources. “[A]nd in desperation ‘broke camp’” when the parents were forced to dissolve their household to split up and live with relatives far from home. In his new surroundings, Bill Thompson shared an unheated attic with his brother, Don. The father, despairing, crushed by his inability to find the work that could reunite him with wife and children, slowly drifted out of Bill Thompson’s reach.

At Franklin Junior High School, he discovered a love and a knack for journalism. Contrasting points of view with faculty overseers prompted Thompson to found a rival newspaper, the Verbal Burp. Motto: “Why burp when you can buy one.”

The paper’s instant success swiftly brought faculty censure. He immediately pushed the button of his youthful philosophy to the fore: “put thine head down and plow straight ahead.” Pressured by non-amused school powers the paper closed, anyway. Over time, he admits, bullheadedness and stubbornness were replaced with “perseverance and persistence.”

He became a first-rate football end, served as an orderly in a lunatic asylum. He worked the night shift at Kraft Cheese Company. By 1942, the war had cast its long shadow over friends and associates who started to drift in increasing numbers into military service. Thompson followed, choosing the Navy’s V-5 program and life as an Aviation Cadet. When that ambition failed, he promptly looked elsewhere around the Navy.

Washing out of the V-5 program “was a stroke of luck” because of the V-12 program he entered, ending with a commission on July 9, 1945. The “Burp” and a high level of literacy were not qualifications the Navy surrendered lightly. In the process, he met Dorothy Elizabeth zum Buttel, the girl from Sheboygan who has remained by his side for more than sixty years, and counting.

At sea and with shore assignments from Guam to the Armed Forces Information School at Carlisle Barracks [now at Ft Meade, Maryland and renamed Defense Information School], to Washington and elsewhere, spiced with an alphabet soup of foreign ports, Thompson matured as a naval officer and as a public information officer. He observed at first hand the Cold War, Korea, and Vietnam eras and their effect on the Armed Services, especially the Navy.

Add a dash of the perfidy that often awaits those assigned to duty in the Pentagon, and you get a brilliant career overlaid by the signal events of most of the 20th century. It was Bill Thompson who persuaded the Navy to change the job description from Public Information to Public Affairs. “Information” was a misnomer, Thompson argued. We did “more than distributing information to the public . . . we were involved in community relations . . . and were also responsible for internal relations communicating with our Navy personnel and dependents.”

Along the way, he worked with some of the personalities who defined the era, including Bob Hope, John F. Kennedy, and Jim Stockdale. He forged a particularly close friendship with Admiral “Bud” Zumwalt, who intently set about breathing new life into a fustian naval establishment that did not always agree with him. Junior officers generally adored him. Zumwalt’s famous communications with our global Navy inspired my Navy unit in Massachusetts to stage a Land Lobster Race. “Z-Gram” won by an antenna length.

Less compelling were his contacts with the perpetually dyspeptic Admiral Hyman Rickover who demanded of Thompson after becoming the Public Affairs community’s first Chief of Information, “What makes you think you are qualified to be in that job?” he said. When Thompson politely replied, he screamed, “Don’t get smart with me. I’ll have you fired!”

Repellent on a broader scale were the uprisings aboard the carrier USS Kitty Hawk and fleet oiler, USS Hassayampa. On the carrier, a group of black enlistees gathered to protest an inquiry about an apprentice seaman for offensive behavior ashore. In the ensuing melee, 60 personnel were injured. A few days later, aboard the oiler, a dozen black ratings told the executive officer that they would not sail unless money allegedly stolen from one of the group was returned. Five white sailors were beaten.

The media had a field day.

Inventive and with more than enough mettle to survive cultural earthquakes, arduous sea duty, nettlesome senior officers and the rest of what the 20th century threw at him, William NMI Thompson survived and even triumphed. In retirement, he took on the job of creating a national memorial for the sea services in the center of the nation’s capital. Arguably, Hannibal had an easier task coaxing his elephants across the Alps. Thanks to Thompson, whenever the spirit moves my progeny, they can look at a photo of their ancestor and his bride, and read what he thought about his life in the U.S. Navy.

On another personal note, Admiral Thompson accepted me into the public affairs community and gave me a job: Navy Bicentennial Coordination Officer. During the interview, I said something that made him laugh. That’s the trick: make ’em laugh.

With the help of some very large “elephants” (the blunt ADM Worth Bagley, VCNO; elegant, brilliant Captain Brayton Harris; Thompson’s successor in the CHINFO job, RADM Dave Cooney and the formidable, indomitable Secretary of the Navy himself, Bill Middendorf) the Navy captured the bicentennial celebrations hands down.

There is no shortage of military autobiographies that earn acclaim, and high regard sometimes larded with thinly veiled envy by former colleagues. Only a few memoirs transcend the divide to capture a reader’s respect and affection blended with the undoubted certainty that here is the story of a remarkable man, also a very modest man, who achieved great things for his Nation and Navy. Gumption is that book. No one who gained CHINFO’s inner-sanctum in the years to follow displayed as much force of intellect, talent, character, and personality as Bill Thompson.

On the editing side, a good index would be a big help also a more generous sprinkling of dates to make it easier to anchor events.

Eric Dietrich-Berryman resides in Virginia Beach, VA.