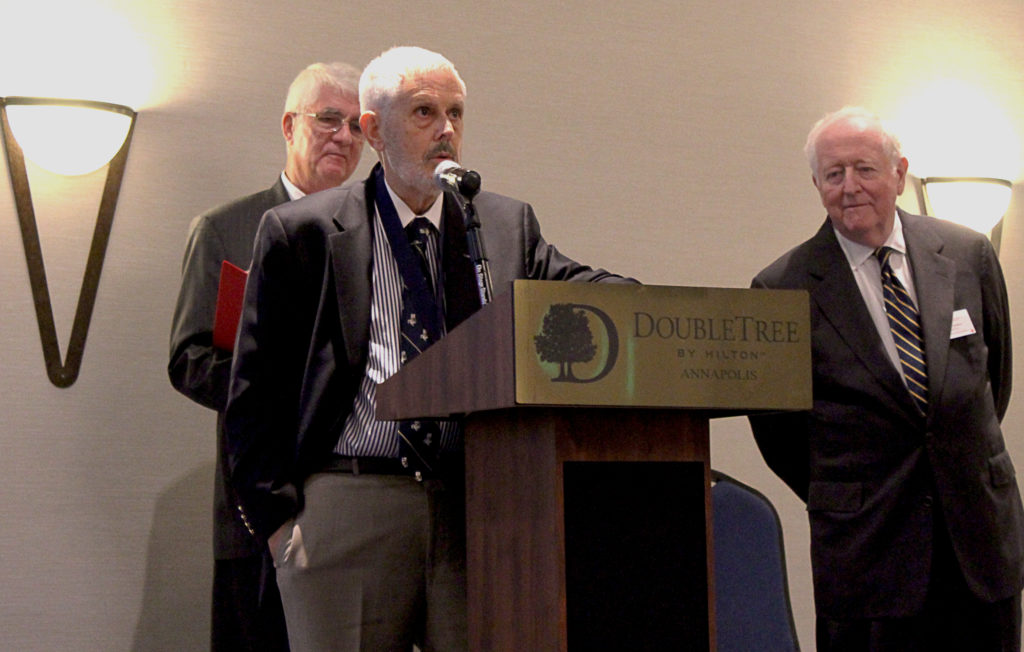

Dr. Kenneth J. Hagan offers remarks after accepting the Knox Award (NHF Photo by Matthew T. Eng/Released)

This past Friday, the Naval Historical Foundation held a special banquet honoring the myriad accomplishments of this year’s Commodore Dudley W. Knox in Annapolis, Maryland. The banquet also served as the final event of this year’s McMullen Naval History Symposium. Two of this year’s recipients, LCDR Thomas J. Cutler and Dr. Kenneth J. Hagan, were in attendance on Friday evening to receive the award in front of an energetic crowd of colleagues and family. The third recipient, Dr. Dean C. Allard, unfortunately could not attend due to health issues.

Dr. David A. Rosenberg, Class of 1957 Distinguished Chair of Naval Heritage at the United States Naval Academy, led a reflective roundtable discussion with Dr. Hagan and LCDR Cutler about their experiences working in naval history. The following are excerpts of each of their responses to Dr. Rosenberg’s introspective questions:

1. When did you choose to write naval history?

Hagan:

“I had little choice. My mentor at Claremont Graduate School, Charles Campbell, did 19th century America. I asked (him) what the Navy was doing as an instrument of foreign policy throughout much of the 19th century, and he said there had not been a great deal written about that, and therefore I began my research on my dissertation for my dissertation on the Navy of 1877 to 1887.”

Cutler:

“I guess if you believe in destiny, you might look back to when I was a child growing up in Baltimore. We used to play make believe games as kids in those days [ . . . ] we played cowboys and indians, etc. When we played war, everybody would pick a rank of what they wanted to be. Some would be a Sergeant or a Captain. I’m not making this up…even though we were doing land warfare in the alleys of Baltimore, I chose to be a Lieutenant Commander. The only regret i have was that I didn’t choose Admiral back then.

The Navy is a tough job, but it can be a wonderful job. There are challenges. Sometimes when those things would start to get me down I would remember reading biography of John Paul Jones and I would think, “if they could do it, I can, too.” it was that kind of thing. Thats why history is so important. It’s a leadership tool and an inspirational tool. Qhen used properly, it can get you through some tough times.”

2. What impact did the US Naval Academy have on your teaching of naval history. Did it change, especially since you were both naval officers?

Hagan:

“Being a naval officer in the history department as a reservist was in some ways difficult. There were a large number of civilians at the time that I came there who had not served at all. I sensed some degree of apprehension and resentment because I was straddling two fences. I eventually chose one fence.

I always felt that I was very happy to have been in the Navy while teaching. I think that the midshipman appreciated. I know I felt more comfortable with the midshipman because of my naval service. I suspect that I was less comfortable with the civilians. When I came there, Ned Potter was still there with the veterans of WWII. That raised another dilemma – the seapower course when I arrived in 1973 was still about the Navy in the Pacific in WWII. Twelve of sixteen weeks were devoted to it.

I wanted to teach broader aspects of the Navy like the gunboat navy, bureaucratic infighting, and foreign policy. So, Jim Bradford and I changed the course to become an American naval heritage course. I felt more comfortable doing that because I was in the Navy.”

Cutler:

“Coming to the Naval Academy was incredible for me. It solidified why history mattered to me. To come into the history department and stand beside people like him (Hagan) was important. I learned a great deal by rubbing elbows with these historians; these professionals who really knew their stuff. It was inspirational, and it was edifying. On the other side of the podium was the midshipman. There, I felt like there was a responsibility. I understood the importance of history and doing that tough job, and I wanted to convey that to them as well. and I tried very hard to do that.

You don’t cover the material. You inspire them to cover the material. It doesn’t get much better than that.”

3. You both have written significant one-volume histories of the United States Navy. Are there any areas that you think should be better covered that you didn’t have the opportunity to cover?

Hagan:

“The politics of the Navy in the interwar Navy, or the Navy outside of great battles.”

Cutler:

“When I wrote a sailors history – its about SAILORS, and more specifically – to recognize the role of the enlisted sailor – its important to recognize that the sailors are the backbone of the Navy, and I tried to bring that out in a Sailor’s History of the United States Navy.”

4. What would you say to future generations to inspire them in the field?

Cutler:

“The main thing is to read. That’s so easy to say, but it’s all about reading. How did I learn to write? I read. You understand how people write.”

Hagan:

“My advice: study the Army (laughter). Pick a topic that which you can be dispassionate. If you can write something with which you can be dispassionate, because you aren’t emotionally involved in how it turns out, you can be more passionate because you can be more subject. This is why I am sticking with 1890-1921. The only thing I will do with Alfred Thayer Mahan is ignore him.

I would also urge to write naval history in an environment or period in which you are familiar. You can’t put events into context. Know the field, know the period. and pick a period where you are not emotionally committed so you would not skew your interpretation.”

Pingback: Death and Rebirth: 2015 McMullen Naval History Symposium Recap | Naval Historical Foundation

Pingback: 2017 Knox Naval History Award Winners Announced | Naval Historical Foundation